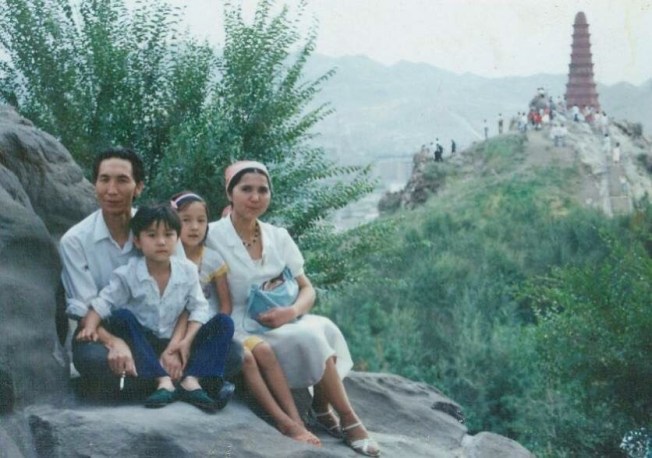

The last time Bahram Sintash saw his journalist father was in 2017. Qurban Mamut, an influential Uyghur editor had come to the United States for a visit but upon his return to Xinjiang in northwest China, he disappeared.

Sintash later learned that his father had been swept up in China’s 2017 crackdown on Uyghurs and other mostly Muslim ethnic groups. China has said its policies in Xinjiang, which involve reeducation camps, forced sterilization, and family separations, are in the name of counter-terrorism, but 51 United Nations member countries have accused the government of “crimes against humanity.”

Mamut, as a prominent intellectual who edited the state-owned Xinjiang Civilization and Tepakkur magazines, was sentenced to 15 years for “political crimes,” according to news reports. According to Sintash, his father’s decades of journalism drew the attention of the Chinese government in its efforts to quash the Uyghur cultural industry.

After initially fearing that speaking out could harm his 74-year-old father’s case, Sintash decided to go public about the detention in 2018; in 2020, he joined the U.S. Congress-funded Radio Free Asia (RFA) in Washington, D.C. to be a “voice of voice-less Uyghurs.”

CPJ spoke with Sintash about his father’s love of journalism, restrictions on the press in Xinjiang, and what he knows of Mamut’s detention. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. The Chinese foreign ministry did not reply to CPJ’s email requesting comment on Mamut’s arrest and sentencing.

What can you tell us about your father’s detention?

I initially thought my father was detained in 2018, but later learned it was actually in late 2017. Communication with my family in Urumqi [the capital of Xinjiang] has been severed since then, with China cutting off our ability to talk in late 2017 and early 2018. My mother told me, “We can no longer talk to you,” leaving me without any information about my father. In September of the following year, I sought to find out what had happened to him. Eventually, one of my neighbors who also lives overseas informed me that my father had been taken away from our neighborhood. This neighbor had heard the news from their family who witnessed my father being taken from his home. I was shocked by this revelation.

At the same time, I was considering what actions to take. I felt that raising my voice was the right decision, but I was extremely cautious. I was unsure of the exact steps to take or the words to use, as anything I said could potentially endanger my father further, given China’s unpredictable actions.

What was the media environment like in Xinjiang before your father’s arrest?

In 2016, a well-known writer, Yalqun Rozi, was detained and later sentenced to 15 years [for attempting to subvert the Chinese state], a fate similar to that of my father. My father visited the United States in January 2017 and stayed for a month, during which time he learned about the detention of Yalqun, a close friend. Yalqun had not been sentenced at that point but was under arrest, likely due to his publication of sensitive topics.

Yalqun had written extensively on various subjects, including Uyghur welfare, and had contributed many essays to my father’s journal, Xinjiang Civilization. Their past collaboration made my father concerned that Yalqun’s arrest might not be an isolated case.

Yalqun’s detention marked the beginning of a broader crackdown on Uyghur intellectuals. China targeted Uyghur intellectuals first in order to more successfully repress Uyghur identity. They began by arresting individuals and then expanded their investigation to a larger network of Uyghurs.

My father understood that this could happen, but we were uncertain about China’s next steps. After 2017, under [Chinese President] Xi Jinping’s leadership, the situation became increasingly dire, reflecting the tense atmosphere of that time.

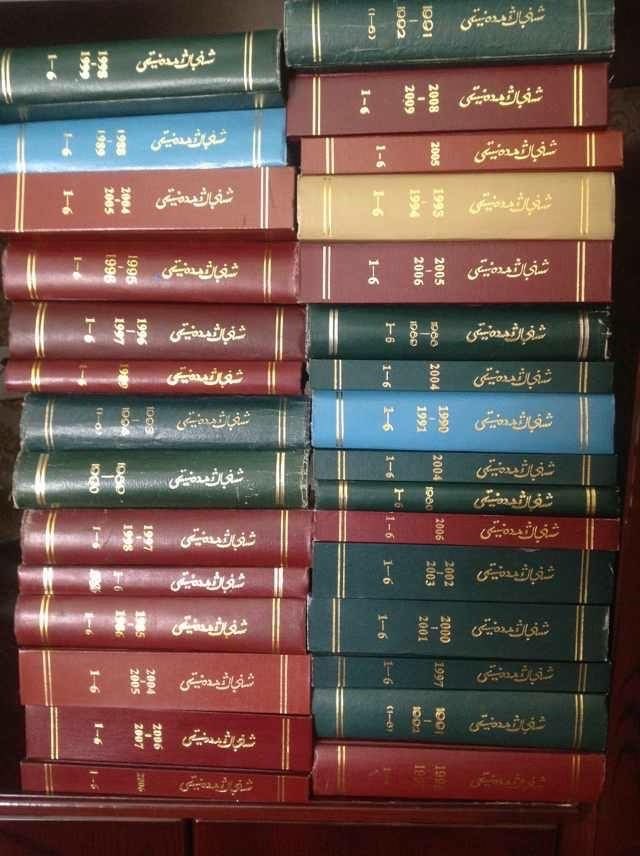

Can you tell us about Xinjiang Civilization, the magazine your father edited from 1985 until 2017?

The content in the magazine mainly focuses on culture, history, current affairs, the identity of Uyghurs, examining the shortcomings of the Uyghur nation and society, and opinion pieces. This was the main content before 2017, primarily when my dad was the sole editor-in-chief.

Interestingly, all the names of the journal’s editorial board members were removed in the third issue of 2017 just half a month before the mass detentions began in 2017. The content of the journal dramatically changed in its last publication. It now became filled with red Communist propaganda. Many of the members on the board were subsequently taken to re-education camps, including my dad. At least two of other members, Abduqadir Jalalidin and Arslan Abdulla, as well as my dad were sentenced to long prison terms.

Before the magazine’s third issue in 2017, its content mainly focused on Uyghur culture and literary works. However, after that issue, it primarily began publishing political content, which mostly revolves around studying Xi Jinping’s ideology. The next editor even wrote an open letter titled “Protecting the security of the ideological sphere is my priority,” in which he promised not to publish anything promoting “separatism,” “terrorism,” or “two-faced” behavior. The letter followed two articles written by Uyghur officials calling the readers to “protect the unity of the nations with hearts and protect the homeland with loyalty.”

What was your father’s relationship to his journalistic work?

My father was the sole editor; there were no secondary editors. However, he had two assistants who could be considered as secondary editors, but their main role was typing and assisting with computer-related tasks. My father worked tirelessly, often putting in 16-hour days. He would work at the office, come home for a quick meal, and then continue working late into the night, spending countless hours at his desk.

Your father was quite well known for his journalism. How was he seen in the Uyghur community?

My father was an exceptional teacher, not through writing himself, but by curating and compiling works from other writers. He focused on selecting the right topics, aiming to present the truth without imposing his own opinions on the journal.

He steered clear of politics, especially avoiding any praise of the Chinese Communist Party or spreading its propaganda, which some writers and editors did to secure better positions and ensure their safety. My father, however, sought out authentic voices who could present genuine work, which is why the journal promoted many unknown writers who eventually became famous. The platform allowed them to express the truth.

While my father didn’t publicly express his own views, he was frequently interviewed on TV talk shows due to his extensive knowledge of Uyghur culture. These appearances contributed to his fame. During the 1990s and 2000s, there was a period when Uyghurs enjoyed a degree of freedom to discuss their identity, language, and other aspects of their culture — a stark contrast to the current situation.

Did your father face retribution for his journalism before his imprisonment?

My father was called in for questioning in 2004, although he didn’t face persecution or punishment. This was related to an opinion piece published in his journal about the Uyghur language. At that time, Xinjiang authorities were starting to phase out the Uyghur language from schools and universities, replacing it with Chinese in subjects like mathematics and other majors.

The writer of the piece was arrested, and my father was questioned by the security bureau and China’s intelligence department. To avoid worrying us, my father never shared the full details of what happened.

You believe your father was arrested for his journalism. Why?

After his retirement in 2011 [from Xinjiang Civilization], my father didn’t stop working. He continued to serve on the editorial board of Xinjiang Civilization, and became the head editor of a newly established magazine called Tepakkur. The magazine, published by the state-run Xinjiang Juvenile Publishing House, or Chiso, gained popularity due to my father’s reputation. “Tepakkur” means “think.” My father, invited to be the editor-in-chief, established this magazine to have more freedom and flexibility in selecting topics.It was not available digitally, only in print, and this was just before the mass arrests began around 2014-2015. As a result, I don’t have a copy and haven’t read the articles, but the journal was well-regarded by its readers.

Can you tell us about your work at RFA? Has your father’s imprisonment made you rethink your personal safety, especially while covering Xinjiang?

I joined RFA because my fear diminished as I became more vocal in advocating for other Uyghurs. I couldn’t remain silent; I had to speak the truth. My mindset became open, ready to face any challenge. Many Uyghurs, concerned for their safety and their families’, avoid RFA and don’t pursue journalism there. But for me, there were no limits. I saw RFA as the only true voice for Uyghurs worldwide, so I joined to work for my people.

As for my efforts to free my father, it’s been an emotionally challenging task. I’ve been in constant communication with organizations, governments, NGOs, and even the United Nations, explaining my father’s situation and speaking to the media. My work extends beyond my father to all Uyghurs and our culture, which I learned to preserve from my father.

Editor’s note: CPJ did not include Qurban Mamut in its previous prison censuses because its researchers at the time could not confirm that his arrest was journalism related.