Editor’s note: In 2019, CPJ published a new database of attacks on the press. The project included a one-time revision of historical imprisoned numbers to clean up duplication; count people from the date of their arrest rather than the date CPJ learned of their case; and retroactively apply the data methodology as consistently as possible. With the single database, numbers are liable to continue adjusting each year as CPJ learns of arrests, releases, or deaths in prison. For the most recent data, see cpj.org/data/imprisoned/.

At least 81 journalists are imprisoned in Turkey, all of them facing anti-state charges, in the wake of an unprecedented crackdown that has included the shuttering of more than 100 news outlets. The 259 journalists in jail worldwide is the highest number recorded since 1990. A CPJ special report by Elana Beiser

Published December 13, 2016

More journalists are jailed around the world than at any time since the Committee to Protect Journalists began keeping detailed records in 1990, with Turkey accounting for nearly a third of the global total, CPJ found in its annual census of journalists imprisoned worldwide.

Amid an ongoing crackdown that accelerated after a failed coup attempt in July, Turkey is jailing at least 81 journalists in relation to their work, the highest number in any one country at any time, according to CPJ’s records. Turkish authorities have accused each of those 81 journalists–and dozens more whose imprisonment CPJ was unable to link directly to journalistic work–of anti-state activity.

The global total of 259 journalists jailed on December 1, 2016, compares with 199 behind bars worldwide in 2015. The previous global record was 232 journalists in jail in 2012.

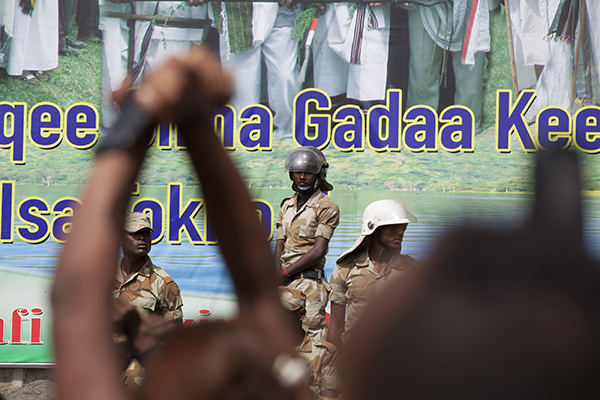

After Turkey, the worst offenders in 2016 are China, which had jailed the most journalists worldwide in the previous two years; Egypt, where the total rose slightly from 2015; Eritrea, where journalists have long disappeared without any legal process into the secretive country’s detention system; and Ethiopia, where longtime repression of independent journalists has deepened in recent months.

This year marks the first time since 2008 that Iran was not among the top five worst jailers, as many of those sentenced in the 2009 post-election crackdown have served their sentences and been released.

CPJ identified eight journalists in Iranian prisons, compared with 19 a year ago. However, Tehran is still sending journalists to jail, including filmmaker Keyvan Karimi, who is serving a sentence of one year in prison and 223 lashes in relation to his documentary about political graffiti, “Writing on the City.”

In Turkey, media freedom was already under siege in early 2016, with authorities arresting, harassing, and expelling journalists and shutting down or taking over news outlets; the unprecedented rate of press freedom violations spurred CPJ to launch a special diary, “Turkey Crackdown Chronicle,” in March. The pace of arrests exploded after a chaotic attempt failed on July 15, 2016 to oust President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in a military coup. In the wake of the overthrow attempt—which the government blamed on an alleged terrorist organization led by exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen—the government granted itself emergency powers and, in a two-month period, detained, at least briefly, more than 100 journalists and closed down at least 100 news outlets.

Among those behind bars in Turkey are Mehmet Baransu, a former columnist and correspondent for the daily Taraf, who reported extensively on a previous coup plot. He is accused of, among other crimes, obtaining secret documents, insulting the president, and being a member of a terrorist organization. The most recent set of charges against him carry a maximum sentence of 75 years in prison. The journalist’s wife told CPJ that her husband was deliberately kept hungry, held in filthy conditions, verbally abused, and mistreated while being transferred from prison to various courts for hearings.

Also jailed in Turkey is Kadri Gürsel, a columnist and publishing consultant for the opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet, who was detained along with at least 11 others in a raid on the newspaper’s office in Istanbul on October 31 and accused of producing propaganda for two rival groups, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and what the government calls the Fethullah Gülen Terror Organization (FETÖ). The investigation into Cumhuriyet has been sealed by court order, so defense lawyers and the public have limited access to the state’s evidence.

Turkish authorities have also subjected Kurdish journalists to a fresh round of arrests and trials, in addition to shutting down pro-Kurdish news outlets. Zehra Doğan—a reporter for Jin News Agency (JİNHA), which is staffed entirely by women–was arrested in Southeast Turkey on the site of urban warfare between Turkish security forces and ethnic-Kurdish fighters. The state’s evidence consists of testimony from people saying they saw Doğan talking with people in the street and taking photos, according to interrogation records and an indictment that CPJ has reviewed.

CPJ examined the cases of another 67 journalists imprisoned in Turkey in late 2016 but was unable to confirm a direct link to their work. In many cases, court documents have been sealed, and in others CPJ could not identify or contact lawyers for the accused—or the lawyers were unwilling to discuss their clients with CPJ, a reflection of the tense atmosphere in Turkey. More than 125,000 people, including public workers such as police officers, teachers, and soldiers, have been dismissed or suspended and about 40,000 others have been arrested since the coup attempt, according to international news reports.

In China, which consistently ranks among the world’s worst jailers of journalists, 38 journalists were in prison on December 1. In recent weeks, Beijing deepened its crackdown on journalists who cover protests and human rights abuses. Huang Qi, publisher of the news website 64 Tianwang, was arrested in November; he has previously spent two long stints in jail for his work documenting human rights violations. After 64 Tianwang reported that police had arrested demonstrators protesting the death of a petitioner they said had been beaten by government supporters, Huang told Radio Free Asia that such reporting “could bring him trouble.”

Protests are also a no-go zone for journalists in Egypt, where CPJ identified 25 in jail. The prisoners include Mahmoud Abou Zeid, the freelance photojournalist known as Shawkan, who has been behind bars without a conviction since 2013, when he was arrested photographing the violent dispersal of a protest in support of ousted President Mohamed Morsi. He is charged with illegal assembly and murder, in a case involving more than 700 defendants. CPJ honored Shawkan with its 2016 International Press Freedom Award; in a video prepared for the awards gala, his mother showed how she cooks his meals every week, hiding fresh fruit under other food because it is forbidden to bring into Tora prison where he is held. Shawkan also has Hepatitis C.

Globally, health problems have been reported for more than 20 percent of journalists on CPJ’s prison census.

In the Americas region, CPJ identified four journalists in prison on December 1 compared with no journalists the previous year.

Other trends and details that emerged in CPJ’s research include:

- Nearly three quarters of those imprisoned globally face anti-state charges. Since 2001, governments have exploited national security laws to silence critical journalists covering sensitive issues such as insurgencies, political opposition, and ethnic minorities.

- The top five worst jailers accounted for 68 percent of journalists imprisoned worldwide.

- About 20 percent of journalists in prison are freelancers. The percentage has steadily declined since 2011.

- The vast majority of journalists in jail worked online and/or in print. About 14 percent worked in broadcast.

- Ethiopia, Panama, Singapore, and Russia were all holding journalists who are foreign nationals. At least two journalists, held by Eritrea and Venezuela, are dual citizens.

- Twenty of the 259 journalists held worldwide are female.

- Countries jailing journalists in 2016 that were not listed on CPJ’s 2015 survey were Cuba, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, Panama, Singapore, Tunisia, Venezuela, and Zambia. In addition, Montenegro appeared on the 2016 census as CPJ became aware for the first time of a journalist arrested in 2015.

The prison census accounts only for journalists in government custody and does not include those who have disappeared or are held captive by non-state groups. (These cases—such as freelance British journalist John Cantlie, held by the militant group Islamic State—are classified as “missing” or “abducted.”) CPJ estimates that at least 40 journalists are missing or kidnapped in the Middle East and North Africa.

CPJ defines journalists as people who cover the news or comment on public affairs in media, including print, photographs, radio, television, and online. In its annual prison census, CPJ includes only those journalists who it has confirmed have been imprisoned in relation to their work.

CPJ believes that journalists should not be imprisoned for doing their jobs. In the past year, CPJ advocacy led to the early release of at least 50 imprisoned journalists worldwide.

CPJ’s list is a snapshot of those incarcerated at 12:01 a.m. on December 1, 2016. It does not include the many journalists imprisoned and released throughout the year; accounts of those cases can be found at www.cpj.org. Journalists remain on CPJ’s list until the organization determines with reasonable certainty that they have been released or have died in custody.

Elana Beiser is editorial director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. She previously worked as an editor for Dow Jones Newswires and The Wall Street Journal in New York, London, Brussels, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The 2016 census has been corrected to reflect the addition of Ethiopian journalist Abebe Wube, who was mistakenly left off the list when it was initially published. The text of the census has also been updated to reflect that Ethiopian journalist Solomon Kebede was released from prison in April 2016.