Journalists have a huge amount of work to do

By Christiane Amanpour

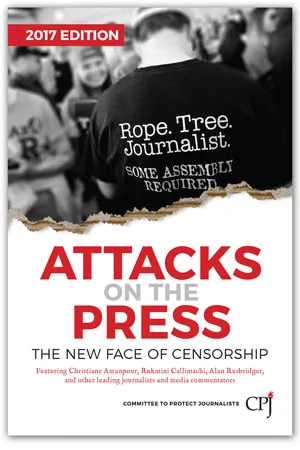

Never in a million years did I expect to find myself appealing for the freedom and safety of American journalists at home. Despite the hostile rhetoric of the U.S. presidential campaign, I hoped that after becoming president-elect, Donald Trump would change his approach to the press.

But I was chilled when among the first tweets Trump sent out after the election was about “professional protesters incited by the media.” Though he later walked back the part about the protesters, he did not soften his stance about the media’s incitement. Though we are not there yet, here’s a postcard from the world: This is how it goes with authoritarians like Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Turkey’s Recep Erdoğan, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, the Ayatollahs, the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, et al.

International journalists know only too well: First the media is accused of inciting, sympathizing and associating, then suddenly they find themselves accused of being full-fledged subversives and even terrorists. They end up in handcuffs, in cages in kangaroo courts, in prison–and then, who knows?

In late 2016, Turkey’s Erdoğan, who has the ignominious distinction of running a country with more journalists behind bars than any other, told my Israeli colleague Ilana Dayan that he could not understand why anyone protested Trump’s election in America, that it must mean they don’t accept or understand democracy. He thinks America, like all great countries, needs a strongman to get things done. But what all great countries need is a free press, and certainly not a strongman who wants to limit their ability to tell the truth. In fact, a great America requires a great, free and safe press.

Because journalism is under siege worldwide, we must appeal to protect the profession itself, including in the country whose free media has historically led the way. To do that, we must recommit to robust fact-based reporting without fear or favor on the issues. We cannot stand for being labeled crooked or lying or failing. We must stand up together, for divided we will all fall.

The historian Simon Schama told me early on that the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign was not about just another election, and that we could not treat it as one. After the election, he told me that if there were ever a time to celebrate, honor, protect, and mobilize for press freedom and basic good journalism, it was now.

Like many people watching from overseas, I admit that I was shocked by the exceptionally high bar put before one candidate and the exceptionally low bar put before the other candidate. It appeared much of the media got itself into knots trying to differentiate between balance, objectivity, neutrality and, crucially, truth.

We cannot continue to give equal play to climate deniers as we do to those who rely on the fact that 99.9 percent of the empirical scientific evidence proves manmade climate change is occurring. I learned long ago, while covering the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Bosnia, never to equate victim with aggressor, never to create a false moral or factual equivalence, because then you are an accomplice to the most unspeakable crimes and consequences. I believe in being truthful, not neutral. And I believe we must stop banalizing the truth. We as journalists have to be prepared to fight especially hard for the truth in a world where the Oxford English Dictionary announced that “post-truth” was the notable word of 2016.

We also have to accept that we’ve had our lunch handed to us by the very same social media that we’ve so slavishly been devoted to. The winning candidate did a savvy end run around us and used it to go straight to the people with whatever version of the truth he chose. That end run was combined with the most incredible development ever–the tsunami of fake news sites, a.k.a. lies–that somehow people could not, would not, recognize, fact-check, or disregard. One of the main writers of these false articles says people are getting dumber, just passing fake reports around without fact-checking. We need to ask whether technology has finally outpaced our human ability to keep up. Facebook needs to step up to stem the flow of fake news, and advertisers need to boycott the lying sites. The truth cannot be treated as a relative term.

Wael Ghonim, one of the fathers of the Arab Spring, which has also been dubbed the social media revolution, put it this way: “The same medium that so effectively transmits a howling message of change also appears to undermine the ability to make it. Social media amplifies the human tendency to bind with one’s own kind. It tends to reduce complex social challenges to mobilizing slogans that reverberate in echo chambers of the like-minded rather than engage in persuasion, dialogue, and the reach for consensus. Hate speech and untruths appear alongside good intentions and truths.”

Given the array of challenges facing the free press around the world, including in its historical bastion, the U.S., we as journalists face an existential crisis, a threat to the very relevance and usefulness of our profession. Now, more than ever, we need to commit to real reporting across a real nation, a real world in which journalism and democracy are in mortal peril, including by foreign powers such as Russia, paying to churn out and place false news and hacking into democratic systems in the U.S. and allegedly in crucial German and French elections, and hacking into the institutions of many other countries, too.

We must also fight against a post-values world and against this “elitist” backlash that we’re all bending over backwards to accommodate. Since when are American values elitist? They are not left or right values. They are not rich or poor values, not the forgotten-man values. Like many foreigners I have learned that they are universal. They are the values of the humblest to the most exalted Americans. They form the very fundamental foundation of the United States and are the basis of its global leadership. They are brand America. They are America’s greatest export and gift to the world.

Lying and promoting lies is not an American value. Yet the 2016 presidential election actually embraced so much that is untrue, and created an unprecedented paradigm: Very few ever imagined that so many Americans conducting their sacred duty in the sanctity of the voting booth, with their secret ballot, would be angry enough to ignore the wholesale vulgarity of language, the sexual predatory behavior, the deep misogyny, the bigoted and insulting views, and the deliberate falsehoods that were sometimes followed by lies claiming they had never been said, even when they were recorded on video. Governor Mario Cuomo said you campaign in poetry and govern in prose. Perhaps the opposite will be true this time around. If not, we must all fight as journalists to defend and protect the unique value system that makes these United States, and with which it seeks to influence the world.

After the election, there was a “Heil, victory” meeting in Washington, D.C., which represented a move about as far from traditional American values as you can get. Why aren’t there more stories about the dangerous rise of the far right here and in Europe? Since when did neo-Nazism and anti-Semitism stop being a litmus test in this country? We must fight against normalization of the unacceptable.

A week before the heated Brexit referendum in the U.K., the gorgeous, young, optimistic, idealistic, compassionate Minister of Parliament Jo Cox, a Remainer, was shot and stabbed to death by a maniac yelling “Britain first.” At his trial, the court was told the accused had researched information on the SS and the KKK. Her husband, Brendan, now raising their two tiny toddlers, expanded for me on an op-ed he’d written:

“Political leaders and people generally must embrace the responsibility to speak out against bigotry. Unless the center holds against the insidious creep of extremism, history shows how quickly hatred is normalized. What begins with biting your tongue for political expediency, or out of social awkwardness, soon becomes complicity with something far worse. Before you know it, it’s already too late.”

What are we to do? Beyond reporting the truth, and not normalizing the unacceptable, we must ensure that the war of attrition in this country comes to an end. The presidential election was very close, but it illustrated a sharp divide. And it both revealed and tapped into a remarkably deep well of anger. Are we in the media going to keep whipping up that war, or are we going to take a deep breath and have a reset?

These things not only matter for the future of the U.S. and the country’s media. They matter to us out there abroad. For better or for worse, the U.S. is the world’s only superpower, and its political and media examples are emulated and rolled out across the world. We, the media, can contribute either to a more functional system or to deepening the political dysfunction.

Which world do we want to leave our children?

American politics has driven itself into poisonous partisan and paralyzing corners, where political differences are criminalized, where the zero-sum game means that in order for me to win, you have to be destroyed. What happened to compromise and common ground? That same dynamic has infected powerful segments of the American media, as it has in Egypt, Turkey, and Russia, where journalists have been pushed into political partisan corners, delegitimized, and accused of being enemies of the state. Journalism itself has become weaponized. We cannot allow that to happen.

We all have a huge amount of work to do, investigating wrongdoing, holding power accountable, enabling decent government, defending basic rights, actually covering the world. As a profession, we must fight for what is right. We must fight for our values. Because bad things do happen when good people do nothing.

In the words of the great civil rights leader, Congressman John Lewis: “Young people and people not so young have a moral obligation and a mission and a mandate to get in good trouble.”

So, let’s go out and make some trouble. Let’s fight to remain relevant and useful. Let’s reveal lies for what they are, and fight for the truth. Because the future of the world depends on it.

Christiane Amanpour is CNN’s chief international correspondent, anchor of the network’s global affairs program “Amanpour,” a senior adviser to CPJ and a goodwill ambassador for press freedom and safety at UNESCO. In November 2016, she received CPJ’s Burton Benjamin Memorial Award for her extraordinary and sustained achievement in the cause of press freedom. This report was adapted from her acceptance speech.