Pia Randa is in Philippine leader Rodrigo Duterte’s crosshairs. At presidential press conferences, Duterte has repeatedly singled out the reporter by name and referred to Rappler, the news site where she works, as “fake news” and her reporting as “corrupt” and “biased” against his administration.

Ranada told CPJ that Duterte has called her a “traitor,” and not a “true Filipino,” and threatened that “something” would happen to her if she traveled to Davao, a city where he served as mayor for over two decades and which is currently renowned as the nation’s murder capital. She said she has also received anonymous rape, death and other threats in emails and via social media over her critical coverage.

In February, Duterte’s government banned all Rappler journalists from reporting from Malacañang, the presidential palace. “Aside from making it extra emotionally draining and sometimes scary to write something critical about him, it also sends a message to other reporters that this could happen to them,” Ranada said.

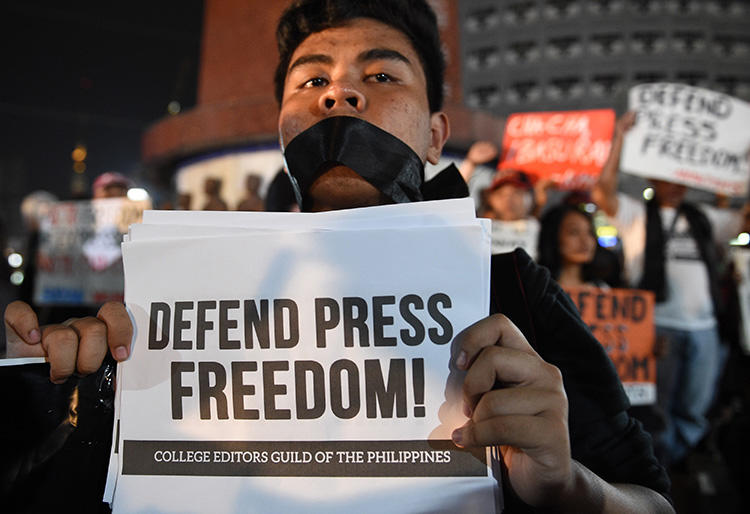

Reporters, editors and advocates told CPJ in May that the government is using a tri-pronged approach to intimidate the press via verbal assaults, social media attacks, and threats to withdraw media groups’ licenses or hit their commercial interests to encourage self-censorship when reporting on sensitive issues. Those issues include Duterte’s controversial drug war, a campaign that rights groups say has led to over 12,000 killings since he took office.

Ranada and Rappler are prime targets of Duterte’s media intimidation tactics, a campaign of harassment to undermine the credibility of critical independent reporters and public confidence in the press.

The Securities and Exchange Commission ruled in January that Rappler violated constitutional provisions banning foreign ownership and control of media organizations and ordered its registration revoked. Rappler–whose founder and executive editor Maria Ressa is CPJ’s 2018 Gwen Ifill Press Freedom awardee-has been allowed to continue operating while the ruling is under appeal.

The harassment sent a warning to other media organizations that they could be next if their reporting is perceived as overly critical of Duterte’s government, journalists, editors and press freedom advocates said.

“Some media think we are getting what we deserve. In this manner [Duterte] has divided us,” Ranada said. “The media who are supportive [of Rappler] are too scared to speak out for fear of reprisal. I don’t blame them.”

Duterte set a threatening tone from the start of his presidency, saying in reference to the case of a murdered journalist in his hometown of Davao: “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination if you’re a son of a bitch.” At the same press briefing, he said, “Freedom of expression cannot help you if you have done something wrong.”

“From day one, the president rationalized the killing of journalists,” said Inday Espina-Varona, a reporter of over three decades and former chairwoman of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), a local press freedom group. “That set the tone for his relations with the media.”

The stakes for controlling the narrative are high for Duterte’s government. The Hague-based International Criminal Court said earlier this year it has started a preliminary inquiry into whether Duterte’s drug campaign caused crimes against humanity.

Underscoring the sensitivity, police visited the Reuters’ bureau in Manila to check reporters’ credentials, in what local journalists and advocates described as an unprecedented act of intimidation. Earlier this year, Reuters won a Pulitzer Prize for its exposé on the drug war.

Duterte’s antagonism towards the media is often perpetuated by pro-government supporters who frequently criticize and sometimes threaten reporters online and over social media, especially in response to their coverage of Duterte’s war on drugs and other controversial policies.

Several journalists told CPJ they have received threatening messages via social media or online over their critical coverage.

“It’s not 10 silly people, it’s a flood, hundreds and thousands in a day,” said Espina-Varona, a regular contributor to local broadcaster ABS-CBN. “It’s bad enough that they highjack lucid [online] conversations on important news topics, but when the criticism turns to threats it also starts to take a psychological toll.”

Felipe Villamor, a Manila-based reporter for The New York Times whose social media accounts are swarmed with critical comments, said he believes many of the comments are manufactured through an algorithm and disseminated on a loop under false user names to create the illusion of a mass pro-government response. “Many of the comments use the exact same language, but from different users,” said Villamor. “It has the hallmarks of a state-funded troll farm.”

Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza, head of Rappler’s research and content strategy, says the site’s internal monitoring and analysis of the comments shows that many are spread via “sockpuppets”, or fake online users. She said the site’s comment boards and reporters’ social media accounts are deluged with attack words, including “presstitutes,” “biased,” and the local language word for paid, in what they believe is an attempt to undermine Rappler’s credibility.

Pro-Duterte social media “influencers” –some of whom now work as government spokespeople and advisers–often follow the president’s lead by producing and disseminating online memes and other crude caricatures of reporters he singled out for criticism. One meme with nearly 250,000 views portrayed Ranada with a Hitler-like moustache as she asked a question of Duterte at a press conference.

The change in tone in online forums coincided directly with Duterte’s rise to power in mid-2016 and caught many of the news group’s reporters and administrators by surprise, says Stacy de Jesus, Rappler’s head of social media. She said that some of reporters sought trauma counseling and others left the news group altogether due to fears for their safety.

Rappler’s social media team spends much of its working time on “crisis management” to counter false claims and criticism spread online against its reporting. “It’s meant to wear you out so can’t do your job anymore,” said Bagayaua-Mendoza. “It’s really an attack on the entire media industry.”

The political opposition is looking into whether the government may have diverted funds from public relations budgets allocated to Duterte’s Communications Office to finance “covert pro-government trolling operations,” opposition senator Antonio Trillanes said.

The call for an investigation comes in response to a Commission of Audit report released in May that found alleged anomalies in the allocation of a 1 billion peso (US$18.7 million) budget allocated to promote the Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit held in in Manila in late 2017.

“The information that we are getting is that there are paid trolls, there is a troll farm that is operating covertly,” said Trillanes. “They handle thousands of fake accounts to create impressions that are consistent with the interests of the Duterte administration.”

Duterte’s spokespeople have denied that the government maintains “troll farms” aimed at intimidating and harassing reporters. Calls from CPJ to government spokesperson Harry Roque went unanswered. The Secretary of the Presidential Communications Operations Office, Martin Andanar, did not immediately reply to CPJ’s emailed request for comment.

Some journalists said they fear Duterte may move more overtly against big media groups as pressure builds on his administration. Duterte last year said he would ask Congress to block the renewal of local broadcaster ABS-CBN’s franchise–due for renewal 2020–for allegedly failing to run his political advertisements.

Duterte has also dangled threats against the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the country’s largest circulation independent English language daily. In public speeches, Duterte claimed the paper’s owner, the Prieto family, failed to pay the full amount of taxes allegedly owed on a downtown Manila property and that the Inquirer owed 8 billion pesos (US$150 million) in back taxes.

Nestor Burgos, the Inquirer’s presidential palace reporter, said the president’s rhetoric makes his job more difficult because government workers and supporters, particularly those close to Duterte, have started to deny him access to sources and information. He has also come under threat on social media, with Duterte’s supporters claiming to know where he lives and that he should “be careful with his life.”

“Malacañang keeps on saying that the president’s occasional tirades to the press– to the Inquirer, to Rappler, to ABS-CBN– has not violated press freedom because he has not detained any journalists, that it is just his casual language,” said Burgos. “But we journalists, especially those who work for companies he has berated, are exposed to attacks from his defenders. We are under constant threat.”

[Reporting from Manila]