Violence against provincial journalists, self-censorship, and the rise of paid news were the leading press freedom concerns cited by editors and journalists that I met with during my recent visit to India. But for Shubhranshu Choudhary, known as Shu, it’s the ban on radio news that most concerns him. He believes the ban is fueling India’s long-simmering Maoist insurgency, and he’s fighting back, using mobile phone technology to bring independent news to the tribal regions where the Maoists operate.

India’s media is incredibly lively and booming. There are at least 60,000 print publications in the country, and the major cities often boast half a dozen competing dailies. All-news cable stations have sprung up throughout the country, offering a mix of political and business coverage.

But radio news is not part of India’s media landscape: Only the government-run All India Radio is authorized to broadcast news on FM. There are no local news or community radio stations. I heard two explanations for the ban. The first was that the Indian government wants to maintain control over radio because of concerns that irresponsible programming could fuel religious tensions. The second is simply that authorities have been slow to dismantle the government radio monopoly.

Regardless, the effect is that in a country with hundreds of different languages and a literacy rate of around 65 percent, a large portion of Indian’s 1.2 billion people do not have access to independent news and information.

In the tribal areas of Chhattisgarh state, villagers tell Choudhary that they have no voice in the media and therefore no way of effectively communicating with each other or making their concerns known to policymakers in the state capital or New Delhi.

Most people in the region where Choudhary works are illiterate and have no electricity. All India Radio is not broadcast in Gondi, the local language. Print reporters, says Choudhary, write for regional and national papers and do much of their reporting by phone. “Reporting is completely one-sided,” Choudhary explains. “You get your reports from police sources and you don’t need to go the villages.”

Choudhary believes that feelings of isolation and marginalization fuel the Maoist insurgency. Known as “Naxalites” for the town in West Bengal where the insurgency began four decades ago, the Maoists are active today in a large swath of India’s tribal belt that stretches over six states. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has declared the Naxalites one of the greatest threats to India’s security.

Choudhary, a former BBC producer and Knight International Journalism Fellow has worked with Microsoft and MIT to develop new a system that allows tribal villagers to use their mobile phones to disseminate and receive news. It works like this: Villagers who want to report news call a phone number and leave a recorded message in their local language. The information is then verified and disseminated via mobile phone, SMS message, and a Web site, Cgnet.

“We’re excited about voice in general as an interface in low-income communities,” says Bill Thies, a researcher with Microsoft in Bangalore, who helped develop the project. Since it launched in February, more than a thousand villagers in Chhattisgarh have called in with their news tips and to access the information via cell phone.

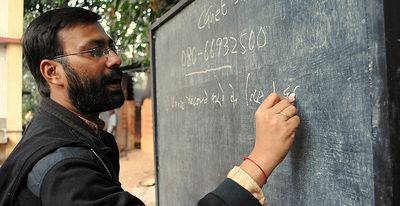

“Our role technologically in this is to make it as easy as possible,” says Choudhary, who has been training villagers to function as citizen journalists. “We want to demystify the media. Journalists think they are god’s gift to man. It’s really pretty simple to be a journalist. You just push a button and talk.”

Mobile phone technology is empowering poor people not just in India, but also in African villages and Latin American slums. If Choudhary succeeds in his ambitious goal of using mobile phones to circumvent traditional media, his project it could have an impact in the many places around the world where radio is either unavailable or not responsive to the needs of the local community.