The headquarters of Le Soir in the center of Brussels, two blocks away from the Parliament, look serene in the spring sunshine. No sign of violence scars the glass and stone facade. But the leading Belgian francophone daily, the flagship of the Rossel media group, has suffered a concussion. On Sunday a wave of hacking attacks rocked the paper. At 07:00 p.m., the hottest moment of the day when articles were pouring in and had to be published on deadline, the Newsgate data center started to slow down, the Wifi was disabled, the journalists’ professional and personal emails were neutralized. The paper– where I am a columnist–immediately took emergency measures, separating the Internet from the intranet, to counter the attack and prevent the hackers from taking over the websites.

The attack also hit the group’s other properties: the Sud Presse papers, a major regional chain in Southern Belgium, and La Voix du Nord, the third largest regional paper in France. The attack stopped two hours later and the paper eventually was off the presses with some delay, but the technical staff had to work until 4:00 a.m. before things were considered stabilized.

The following day a new attack started but was quickly stopped. In the following hours, according to press reports, the attackers bombarded other Belgian newspapers with distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks: La Libre, a center-right quality paper, the tabloid La Dernière Heure, as well as L’Avenir, an important regional chain. The authors of the attacks did not make any political claims and did not post messages on the papers’ websites. @SquadLinker, a group that claimed in a tweet to be behind one of the attacks, communicated to Le Soir on Twitter that they wanted to show “how unacceptably fragile information was in terms of security.”

DDOS attacks against the media are common, and they are usually countered swiftly. But the intensity of the attack on Sunday and its extension to a string of newspapers brought to the fore a number of issues which are bound to affect newsrooms’ attitudes. Hacking does not hit or blow up buildings, but it can still create an atmosphere of vulnerability and intimidation. Questions such as, “Why were we targeted? Was it because of our editorial positions on sensitive and controversial issues?” pop up immediately in journalists’ minds and the risk of subduing or avoiding the coverage of some stories to avoid trouble or stave off physical violence is real. Obviously these non-lethal attacks cannot be compared to the savagery of the killings at Charlie Hebdo in Paris on January 9, but the specter of terrorism and self-censorship looms over a profession which understands that it is watched and increasingly in the firing line. After the January unprecedented wave of #JeSuisCharlie solidarity, defiance and bravado have given way to words of caution and responsibility among cartoonists and columnists.

“You cannot avoid asking yourself whether you did something that might have designated you as a target,” one journalist with the Belgian public broadcaster RTBF told CPJ.

But at this stage even if the newsrooms are on edge and wondering when the next attacks will come, they exclude any idea of self-censorship.

“These attacks will not affect our journalistic work and editorial policy,” Le Soir’s foreign editor, Maroun Labaki, told CPJ. “They will not induce censorship. By principle but also because this incident did not lead to the confiscation of the paper by groups posting their own propaganda on our website. The integrity of our editorial work was safeguarded.”

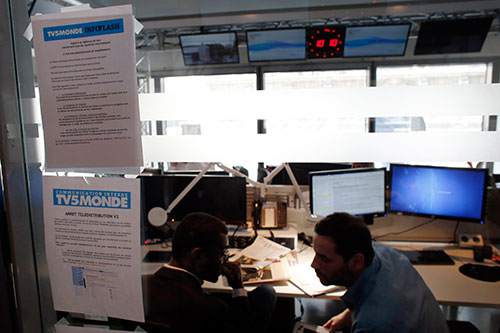

André Crettenand, the news director of TV5Monde, is as adamant in refuting any idea of self-censorship after the April 8-9 massive cyberattack that took the network off the air for 18 hours and hijacked its social media accounts. The hackers, claiming the name of Cybercaliphate and affiliation with Islamic State, had a clear political message: mimicking the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag that became viral after the murderous attacks against the satirical weekly, they posted JeSuisIS (I am IS) on the TV’s websites. It was, in French Prime Minister Manuel Valls’ words, “an attack against freedom of information and expression.”

“At no time there was the slightest suggestion that we should change our editorial line,” Crettenand told CPJ. “After a moment of stupor we focused on producing as soon as we could our next ‘64 Minutes’ current affairs program. We were convinced that TV5 had been targeted because of its global reach and not as a retaliation against its positions or stories. Our news reporting is fact-based and relies on an international team of journalists who by definition are very conscious of what it means to broadcast to a global audience.”

Although police investigators are still analyzing the origins of the attack against TV5Monde, everyone agrees that there is an urgent need to tighten the newsrooms’ security procedures. According to news reports, the cyberattackers were able to slyly penetrate TV5 by phishing three employees who clicked on an infected email in January. A widely circulated video also showed that a password to TV5 YouTube account could be spotted behind the desk of a TV5 journalist during an April 9 interview on the cyberattack. “We focus a lot on our security systems,” Crettenand told CPJ, “but in fact there is always someone, a human being, at the end of the chain, in front of a personal computer. We’ll need a lot of pedagogy.”

It was a wake-up call for the Paris-based network but the lesson, one hopes, has been learnt globally.