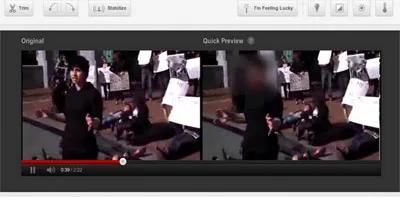

This week, YouTube announced a feature that should catch the eye of video journalists and bloggers working in dangerous conditions. After uploading a video to YouTube, you can now deploy a “blur faces” post-production tool that, in theory, should disguise the visual identity of everyone on the screen. The Hindu newspaper has an excellent how-to guide for their readers.

Face-blurring can be an important security tool for journalists working in regions where witnesses are punished simply for talking to the media. Documenting events in the manner they occur remains the common professional mandate, but in certain instances, such as protecting a vulnerable news source providing sensitive information, blurring a facial image can serve an important purpose. It’s another iteration of the age-old equation of reporting the news while protecting your sources; each journalist must strike his or her own balance.

YouTube’s new feature is not yet perfect and, as Google warns, some hand-holding is needed. The algorithm is optimized for speed more than accuracy, which means that it can sometimes miss a face, or overcompensate. There isn’t yet an interface for choosing which faces to blur or how to disguise voices. It may fail to work on your particular video because the faces are moving too much or the recognition system fails to consistently spot them.

Nonetheless, it’s an important step forward. Google says that it first considered face-blurring after activists requested the feature in a 2011 report compiled by Witness, the organization that uses video and other technology to defend human rights. Face-blurring is something that will be appreciated by thousands of other YouTube users, from protective parents to merry pranksters, but the most compelling argument for its use came from videographers trying to report the news while protecting those they cover.

Journalists need a wider range of such capabilities, and they need them embedded in consumer applications. Consumer Internet services, after all, have become entwined in the lives of professional and citizen journalists. It often falls to individual reporters to use these tools, instead of relying on an editor down the line.

You can’t quite hand off all your security problems to the cloud, though. Google’s face-blurring works only with its copy of the video, not the original source on your local device. There’s some early work by technologists such as the Guardian Project to bring real-time face-blurring to android cameras. But integrating such capabilities into the early stages of a professional work flow is not easy; even computer security experts are still struggling with how to permanently delete recorded content from modern flash storage.

These problems are hard and require long-term research. Face-blurring is one of the first steps in a long road that involves the active involvement and advocacy of companies, technologists, activists, and journalists. Without feedback and support, companies will quietly let these features “bitrot” away. And without active advocacy and criticism, other essential parts of the same emerging security infrastructure will never get built.

Perhaps the best incentive to maintain and improve these privacy-protecting features is if the companies involved sense it’s something they’re actively competing to provide to their customers, rather than generously offering. I suspect it’s just coincidence that Google’s face-blurring was launched the same week as Facebook was being hauled over the coals in the U.S. Senate over its facial recognition, but that fact is almost certainly why YouTube’s addition got some extra coverage. After a decade of consumer Internet services competing on ease of data-sharing, it will be equally rewarding to journalists if they were to start competing on better data protection.