In the reclusive Red Sea nation of Eritrea, the fate of 10 journalists who disappeared in secret prisons following a September 2001 government crackdown has been a virtual state secret—only occasionally pierced by shreds of often unverifiable, secondhand information smuggled out of the country by defectors or others fleeing into exile.

Adding to this trickle of information was a grim account last week detailing the supposed deaths of five journalists in government custody and the whereabouts, health, and detention conditions of the others. The account, broadcast by Radio Wegahta, an opposition station based in Eritrea’s archfoe neighbor Ethiopia, came from Eyob Bahta Habtemariam, described as a former supervisory guard at two prisons northeast of the Eritrean capital, Asmara.

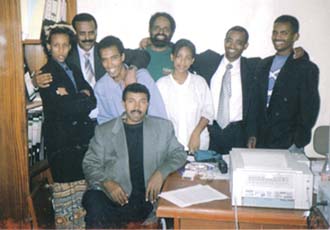

Habtemariam said he began working at Embatkala prison on September 17, 2001. According to Habtemariam, that’s where Fessehaye “Joshua” Yohannes, a co-founder of Setit, once Eritrea’s largest circulation newspaper, and a recipient of CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award, died in 2003. CPJ had already listed Yohannes in its database of journalists killed in the line of duty following unofficial but credible reports of his death. Authorities in Asmara declined to confirm or deny the reports. Yohannes was among the editors of now-banned private newspapers who were thrown in prison barely a week after the 9/11 terrorist attacks; they were jailed in connection with articles calling on the increasingly authoritarian leader Isaias Afeworki to follow the country’s democratic constitution.

Habtemariam went on to say that in 2003 the remaining prisoners were transferred to Eiraeiro maximum-security prison, northeast of Embatkala in a remote desert region. The prison, he claimed, was designed for slow, silent deaths away from public view. Here’s what else he had to say: Prisoners have never been interrogated or told which crimes they committed. They are held in handcuffs and leg irons 24 hours a day and fed one meal a day. Extreme heat was responsible, he claimed, for the June 2003 death of Editor Yusuf Mohamed Ali of the now-defunct Tsigenay newspaper. A year later, Editor Medhanie Haile of Keste Debena died from lack of medical treatment and Editor Said Abdelkader of Admas committed suicide, he claimed. Habtemariam also reported the death of Editor Mattewos Habteab of Meqaleh. According to Habtemariam, the remaining detainees, including Setit co-founder Dawit Isaac, a Swedish citizen who was freed in 2005 but thrown back into prison two days later, are in pitiful physical and mental health. Habtemariam claimed he last saw the prisoners in January of this year, prior to his own escape.

Is this information accurate? After all, it’s being broadcast by an opposition station so there is plenty of reason to question both motives and accuracy.

CPJ called Eritrean officials in Asmara for comment about the allegations. Emmanuel Hadgo, a public relations officer of the Eritrean Information Ministry denied that Eyob Bahta Habtemariam ever worked for the government and rejected the contents of the interview. Hadgo also denied the existence of prisons with such conditions.

But what about the journalists? Are they OK? The spokesman, taking the government’s long-time stance, disavowed any knowledge whatsoever about the imprisoned editors. By the government’s accounting, these human beings have disappeared.

True or not, the newest grim report hit friends and families of the journalists very hard. “This is really painful you know. What can I say? It’s really terrible,” said Yohannes’ friend and the former editor-in-chief of Setit, Aaron Berhane, who narrowly escaped arrest and lives in exile. For Esayas Isaac, Dawit Isaac’s brother living in Sweden, the government’s refusal to provide any information about the conditions of the jailed journalists compounds the anguish. “It’s very difficult to speak to people from the regime. They tell us we’re CIA, we’re sent by the Americans.” During an interview last summer, in response to a question about which “crime” Dawit Isaac had committed, Afeworki declared “I don’t know” but added without elaboration that the journalist had made “a big mistake.”

“If he says Dawit made a ‘mistake’, then he should please let us know what it is. What we’re asking is give him a trial or release him,” Esayas Isaac said. For Afeworki, who indefinitely suspended the country’s constitution after the 2001 crackdown, such legalities do not seem to apply. Speaking of Dawit Isaac in the same June 2009 interview, he declared: “No, we don’t release him. We don’t take [him] to trial. We know how to deal with him and others like him and we have our own ways of dealing with that.”

In fact, among the top nations worldwide whose jails are filled with the most journalists (Eritrea trails only Iran, China and Cuba), Eritrea is the only place where absolutely none of those being held have been charged with a crime, subjected to legal action, or granted visits. As brutal as Iran’s ongoing post-election press crackdown has been, some of the jailed journalists and writers were granted short-term furloughs recently. In China, with a few exceptions, journalists are consistently taken to court. All the Cuban journalists rounded up in a 2003 government crackdown were tried, albeit in summary proceedings. Even North Korea recently gave American journalists their day in court.

Over the years, Eritrean officials have given inconsistent justifications for the September 2001 media crackdown. Officials have variously accused the journalists, many of them former guerilla fighters with Afeworki’s Eritrean Peoples’ Liberation Front, with violating media law regulations, evading mandatory national service, engaging in antistate activities or links with foreign intelligence. At times, officials even sought to erase the jailed journalists from collective memory as when President Isaias responded to a question about Yohannes in a 2004 interview with: “I don’t know him.”

With the president’s absolute grip on state media and the memory of the jailed journalists fading, the government has started rewriting history. In November 2009 for instance, in response to a CPJ inquiry about jailed journalists, Hadgo of the Information Ministry, told the following to CPJ: “I am not aware of any imprisoned journalists in our country. Eritrea is very small and the names you have called I would have known if they were in our prisons, you have wrong information.”

Hadgo went on to say that the only imprisoned Eritrean journalists he was aware of were held in Ethiopia, referring to state TV staffers who have been in Ethiopian custody since 2006. “I am not aware whether they are a live or dead. We heard the whole thing from the news,” he said. It sounds familiar.