CPJ marks one year since Khashoggi’s murder with court action

What did the U.S. government know, and when did it know it? As CPJ enters year two of advocacy to secure justice for Jamal Khashoggi, the Washington Post columnist who was murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018, these are central questions.

Amid continued stonewalling from the Trump administration, CPJ has turned to the courts in our fight for answers. On September 27, we filed a brief in Washington, D.C., District Court seeking U.S. intelligence agency documents indicating whether they knew about threats to Khashoggi before his murder and what, if anything, they did to alert him. News reports indicate they did know of threats, in which case U.S. intelligence agencies had a “duty to warn” him under a 2015 Intelligence Community directive.

Suing was a “no-brainer,” says Alexandra P. Swain, an associate attorney at Debevoise & Plimpton who co-wrote the brief. “This litigation is something that speaks to the heart of CPJ’s mission of encouraging press freedom around the world and protecting journalists’ ability to do their jobs.”

Indeed the stakes go well beyond the Khashoggi case. “We are concerned that additional lives may be on the line,” CPJ North America Research Associate Avi Asher-Schapiro wrote in Lawfare. “If [journalists] find themselves in the crosshairs of authoritarians, will the United States stand by them?”

In late 2018, CPJ and the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University filed a set of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for documents related to the “duty to warn.” The intelligence agencies refused those requests and said they could neither confirm nor deny the existence of such documents for national security reasons—what’s known as a “Glomar” response.

Our lawsuit challenges that response and asks the court to review any relevant documents and determine whether the government’s national security arguments are valid. In the brief, we argue that the public has a right to information about the Khashoggi case and that a Glomar response is wholly inappropriate. Acknowledging whether or not agents warned Khashoggi that he was in danger simply would not reveal intelligence agencies’ sources or methods, the lawsuit argues.

We sense an effort to conceal. “Because of the incredible nature of this case and the international significance of Mr. Khashoggi’s murder, there is some indicia that the government is trying to avoid public embarrassment,” Swain said. CPJ wants to know how far an effort at concealment may have gone. After the brief was filed, news reports surfaced raising questions about whether “the White House may have used the same classification system allegedly misused in the Ukraine matter to help avoid public discussion of Khashoggi as well,” said Jeremy Feigelson, a partner at Debevoise, which is representing CPJ pro bono. The New York Times reported that White House officials seeking to avoid leaks concealed transcripts of delicate calls between President Trump and foreign officials, including members of the Saudi royal family.

“We’d love to see the court hold the government’s feet to the fire,” Feigelson said. “We are optimistic at the end of the day that we will, indeed, see documents.”

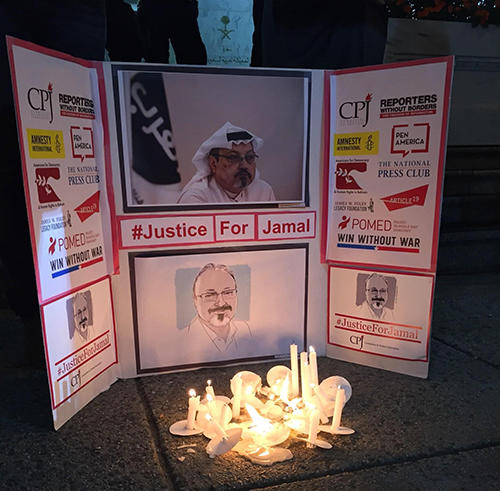

To mark the one-year anniversary of Khashoggi’s murder, CPJ joined a moment of silence at the National Press Club and hosted a candlelight vigil. “We stand outside the Saudi embassy in Washington, D.C., tonight to recognize the loss of a vital journalist and remind the world that we will not rest until there is justice for his murder,” CPJ Advocacy Director Courtney Radsch told the crowd. “This inaction sends the message not just to Saudi Arabia, but to governments around the world that killing journalists is acceptable. It is not.”

CPJ renewed its calls on Congress to pass legislation that requires the Trump administration to disclose the names of individuals involved or complicit in Khashoggi’s murder and that imposes visa sanctions on Saudis officials. “The public deserves to know the truth, and governments around the world must know that the murders of journalists will not go unpunished,” Radsch said.

Sulzberger issues warning about deteriorating press freedom

President Donald Trump’s hostility toward a free press is creating an increasingly dangerous environment for journalists around the world, A.G. Sulzberger, the publisher of The New York Times, said in a September 23 lecture at Brown University that also appeared as a Times op-ed.

“The hard work of journalism has long carried risks, especially in countries without democratic safeguards. But what’s different today is that these brutal crackdowns are being passively accepted and perhaps even tacitly encouraged by the president of the United States,” he said. As evidence, Sulzberger revealed that two years earlier, the Trump administration was poised to turn a blind eye to the imminent arrest of its reporter in Egypt, Declan Walsh.

Foreign leaders have been emboldened, Sulzberger said. More than 50 across five continents have used the term “fake news” to justify attacks on the press. And the leaders of Ireland and Brazil have bashed the media with Trump at joint press briefings. Add Russia, Hungary, and Pakistan to that list, CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon said in a tweet—in displays that do grave harm to press freedom.

Sulzberger laid out a number of ways to protect a free press, including standing up for First Amendment values and supporting good journalism. He also encouraged support for CPJ’s vital work to defend at-risk journalists around the world. If you value our mission, we invite you to follow us on social media, read about the issues on our site, share what you learn with your network, and donate online now.

My colleagues and I at @SevenLetter have been longtime supporters of @pressfreedom and we’re making another contribution today in recognition of the outstanding work being done by @declanwalsh of @nytimes and other journalists facing increased threats every day. https://t.co/EPk0l5Kvcs

— Erik Smith (@ErikSmithDC) September 24, 2019

Protecting women journalists from harassment and threats

CPJ published a series exploring the problem of harassment and safety for women journalists and providing tailored safety information.

The project, led by CPJ Foley Fellow Lucy Westcott, began with a survey of 115 female and gender non-conforming journalists in the U.S. and Canada. The survey revealed widespread unwanted sexual advances, explicit threats of rape and violence, a grinding toll to mental health from such attacks, and a lack of newsroom emergency planning. We also learned the experiences can have a silencing effect on women journalists, many of whom may abandon stories or beats, leave journalism entirely, or retreat from the internet.

In addition to describing the survey findings, Westcott wrote about the particular dangers female reporters face working solo in the field and a growing problem of online harassment that’s often unappreciated by managers. CPJ also updated its safety notes on digital security, including guidelines on how to remove personal information from the internet, how to deal with the psychological impact of online harassment, and DIY digital security guides that provide best practices for protecting yourself online.

The project received significant media coverage, with CPJ giving interviews to CNN Reliable Sources and The Associated Press, and was shared widely, including by Mediagazer, Pew Research Center, American Press Institute, and International Women’s Media Foundation. We also presented our findings at the Excellence in Journalism conference in San Antonio.

Are you interested in learning more about ways to protect women journalists online and offline? Contact us at emergencies@cpj.org.

Haunting images of ‘Journalists Under Fire’

CPJ, in collaboration with United Photo Industries and St. Ann’s Warehouse, put on a special exhibit called “Journalists Under Fire” at the annual Photoville festival in New York City’s Brooklyn Bridge Park. The exhibit features photographs by journalists from around the world who were killed, imprisoned, or threatened in connection to their work.

Displaying powerful examples of the photojournalists’ work along with their portraits and personal stories, the exhibit was inspired in part by CPJ’s book and digital campaign, “The Last Column,” featuring the final articles and photographs of fallen journalists. It also built upon CPJ’s #SafetyInFocus campaign, which highlights the risks photojournalists face in the line of duty.

CPJ’s Emergencies Director María Salazar Ferro spoke during a panel at Photoville about the threats photojournalists face and what they can do to keep themselves safe. “Photojournalists have to work on the front lines—they can’t shoot from a hotel room,” she said, according to a Columbia Journalism Review report.

Photoville attracted 102,900 visitors over two long weekends in September. “Journalists Under Fire” was on display at St. Ann’s Warehouse through October 6.

Impact Tracker

- For years, CPJ has covered Sudan’s detention, harassment, and relentless censorship of journalists in the country. As a peaceful revolution unfolded there this year, CPJ demanded the release of detained journalists and an end to censorship. After President Omar Hassan al-Bashir fell, the interim authority did just that. But whether a new Sudan would commit to protect press freedom remained unclear until this September, when Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok announced that Sudan has signed the Defend Media Freedom pledge, acknowledging that press freedom is key to promoting democracy and development. He spoke at a closed event hosted by the United Kingdom and Canada on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly that included U.K. Special Envoy on Media Freedom Amal Clooney, the director general of UNESCO, and Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian. At the event, Hamdok committed to reforming Sudan’s restrictive media laws and never jailing a journalist again. He said Sudan’s new government would enshrine press freedom, permit unfettered media access, and allow the BBC to reopen.

- Since investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated in Malta in October 2017, CPJ has continuously fought for full justice in her case. Though Maltese authorities charged three people with her murder, the mastermind has not been arrested and no trials have commenced. That’s why CPJ has pushed for an independent investigation in Malta and the European Union. In June, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe issued a resolution requiring the Maltese government to launch an independent public inquiry into the murder within three months. On September 20, Prime Minister Joseph Muscat announced the inquiry and said it must be concluded in nine months, according to news reports. CPJ has concerns about the independence of the commission carrying out the inquiry, and will closely monitor its work.

- In July, CPJ briefed James S. Gilmore, a former governor of Virginia who was recently appointed the U.S. permanent representative to the Vienna-based Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. At that roundtable, we engaged him on key cases and issues of concern, including impunity in journalist murders. We raised similar issues in September at the State Department’s annual roundtable with civil society organizations ahead of the Human Dimension Implementation Meetings, Europe’s largest human rights gathering, where CPJ’s EU Representative Tom Gibson moderated a panel. There, Gilmore stood up for journalists, urging strengthened safety standards for the media and arguing international “disinformation” is best fought through “free expression.”

- On August 27, police in central Equatorial Guinea arrested and detained two journalists, presenter Milanio Ncogo and reporter Ruben Dario Bacale, both of privately owned broadcaster Asonga TV. Ncogo told CPJ he believed their arrests were retaliation for an interview Bacale conducted with a judge who had recently been suspended by the president of the country’s supreme court over a dispute related to an embezzlement case. CPJ spoke with Equatorial Guinea’s information minister, Eugenio Nze Obiang, on September 4, who said he was not aware of the arrests. Asonga TV is owned by Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the country’s vice president and son of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. Ncogo and Bacale were released on September 8 without charge.

- Chinese police in November 2018 detained photojournalist Lu Guang, who for decades documented economic, social, and environmental disruption in China. He was taken into custody while visiting Xinjiang, the center of Beijing’s crackdown on Uighurs and other Muslim minorities. CPJ documented his case, called for his release, and spoke to the media about the injustice of his arrest. On September 9, Lu’s wife, Xu Xiaoli, said on Twitter that her husband was released and allowed to go home “some months ago,” but declined to comment further. Lu has not been allowed to return to the U.S., where he had been living.

Must reads

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Howdy Modi!” event in Houston with President Trump was a raucous affair—in painful contrast to two months of enforced silence in Kashmir, writes CPJ’s Aliya Iftikhar in the Houston Chronicle. After stripping Kashmir of its limited autonomous rule, the Indian government has cut off nearly 8.5 million people from basic news and communications. Meanwhile, India has arrested journalists and made it extremely difficult for them to work in Kashmir, CPJ’s Kunal Majumder reported from Srinagar. “At historic times like this, a free press plays a critical role,” Iftikhar wrote. “Journalists must be able to report without restrictions.”

Working conditions for journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan have hit bottom, CPJ’s Ignacio Miguel Delgado Culebras reports from Erbil and Sulaymaniyah. “Freedom of expression is on the brink of extinction” in Iraqi Kurdistan, said freelance journalist Guhdar Zebari, who has been assaulted, detained, and had equipment seized and broken. “Ever since I started working as a journalist nine years ago, I have been under constant pressure from my family, my tribe, and my community to give up journalism.”

Massive forest fires in Bolivia, which have been nearly as destructive as those in Brazil, have posed enormous challenges for Bolivia’s news media, CPJ’s John Otis reports from Santa Cruz. Journalists often embed with volunteer firefighters, but both the volunteers and reporters often lack training and on-the-ground experience dealing with major fires. Journalists, a cable TV news director said, often arrive without helmets, respirators, or protective boots. “I saw one guy reporting on the fires in shorts.”

CPJ in the news

“Watchdog pushes U.S. to publish ‘Duty to Warn’ Khashoggi files,” Inter Press Service

“Bernie Sanders, impeachment, immigration, Khashoggi,” ABC News The Briefing Room

“How online harassment threatens press freedom,” CNN Reliable Sources

“It’s imperative to capture all sides of the immigration debate. How we did it, during one perilous week,” USA Today

“I wanted immigration detention complex blueprints, but all I got was a hefty legal letter,” The Global Muckraker

“Eff the media,” Fort Worth Weekly

“Dictators and the Internet: A love story,” The Washington Post

“Uganda expands its internet clampdown, stifling the last space for free speech,” World Politics Review

“A Nobel for Sweden’s Greta Thunberg? A tough decision for prize committee,” Reuters

“Why doesn’t the Mexican government protect journalists?” The Globe Post

“Moroccan journalist on trial for an abortion she says she never had,” The New York Times

“Egypt arrests journalists, blocks websites after protests,” AFP

“Eritrea beats North Korea as world’s most-censored country,” Bloomberg

“How long must Eritrea wait for change?” Council on Foreign Relations

“Masked soldiers, barred mosques and constant surveillance: Inside Kashmir under lockdown,” openDemocracy

“No country for dissidents,” Bangkok Post

“Independent Tajik news agency facing ‘apparently targeted disruption’,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

“The case against an investigative journalist shows Tanzania’s Magufuli widening a media crackdown,” Quartz