CPJ has joined with African press freedom groups to urge African leaders to end repression of the media as they celebrate 50 years since the end of colonial rule. We will publish a series of blogs this week by African journalists reflecting on the checkered history of press freedom over that period.

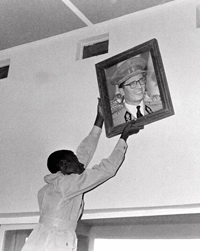

This year is the 50th anniversary of independence for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa from colonial powers France and Belgium. To mark the event, French President Nicholas Sarkozy has invited African leaders to Paris for the July 14 Bastille Day celebrations. One thing that hasn’t changed much in the last half a century is that the presidents and prime ministers on the Champs Elysees reviewing stand can rest assured that media back home will dutifully report on their speeches and appearances.

Countries in French-speaking west and central Africa may have modified the one-party rule and state media monopolies that characterized the region for the first 30 years after independence but only a handful of nations boast a truly independent and critical press.

The euphoria among many local journalists at the fall of the Berlin Wall and an end to Cold War rivalries playing out on African soil was not followed by the hope for flourishing of sustained media freedoms. Instead, the 1990s brought terrible civil wars and genocide in Rwanda. Those political upheavals did not spell good news for press freedom.

In the last decade, private media companies have emerged to challenge the state stranglehold on news and information but European-educated political elites from Dakar to Kinshasa are rarely shaken by serious investigative or critical reporting.

Broadcasters and newspapers controlled or influenced by the state still dominate public discourse. The online revolution that is churning up media landscapes in the Middle East and Asia and giving voice to hitherto unheard writers has not yet reached most of sub-Saharan Africa. There, online news sites and news blogs are in their infancy. Internet use is low, hampered by poverty, poor communications infrastructure, and even frequent power outages. Those domestic blogs that do exist reach only a tiny audience and their subject matter rarely rises above the purely local. In contrast, diaspora French-language websites have become forums for uncensored news, activism and political dissent. These include U.S.-based TamTam.info a leading news site on Niger, Belgium-based Camer.be, a must-read for expatriate Cameroonians, and Canada-based GuinneeNews, which made up for the absence of daily newspapers in Guinea by covering this month’s historic election.

Many older Francophone African journalists lament what they see as a deterioration of standards in journalism including corruption of the profession by political and commercial interests. Young reporters who challenge authority do so often at great personal risk since only a lucky few have the backing of rich or powerful media outlets. French-language African newspapers are based on the same uncertain economic model as their counterparts in the West. In fact the independent ones tend to have tiny circulations, limited to a small number of cities where rates of literacy and income are higher than in rural areas.

In the last 10 years, some authoritarian regimes have become more sophisticated in controlling news, using criminal prosecutions, imprisonment, harassment and intimidation as a last rather than first resort. Where independent or opposition-backed media have emerged, ruling elites now use their deeper pockets to buy the latest technology to modernize old state-controlled outlets or create new ones which shrink the audience for critical voices. A well financed, technically superior newspaper like Les Dépêches de Brazzaville in Congo, or the radio station Rema FM in Burundi, have overshadowed rivals. In countries where press freedom advocates have scored victories, such as the decriminalization of defamation in Ivory Coast for example, governments have fought back. The media group Le Réveil in Abidjan has been slapped with hefty damages for its political coverage in a number of civil libel judgments which it is appealing. Other forms of soft repression include withholding of government advertising, denial of publishing and broadcast licenses and access to capital.

Fortunately the picture is not uniformly bleak. Radio, particularly private and community broadcasts, are a growing force. Market entry is relatively cheap. Radio also overcomes the illiteracy problem and taps into Africa’s oral tradition. Low-range community stations have sprouted in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and private radio is thriving across the region whether as individual businesses or as part of newly formed conglomerates that include print and TV interests.

Another hope for news distribution in the region is the popularity of mobile phones and SMS texting. Without adequate landlines or 4G wireless for Internet carriage, this relatively low-tech medium might play to Africa’s ingenuity for low tech fixes.