Governments and non-state actors find innovative ways to suppress the media

By Joel Simon

In the days when news was printed on paper, censorship was a crude practice involving government officials with black pens, the seizure of printing presses and raids on newsrooms. The complexity and centralization of broadcasting also made radio and television vulnerable to censorship even when the governments didn’t exercise direct control of the airwaves. After all, frequencies can be withheld; equipment can be confiscated; media owners can be pressured.

New information technologies–the global, interconnected internet; ubiquitous social media platforms; smart phones with cameras–were supposed to make censorship obsolete. Instead, they have just made it more complicated.

Does anyone still believe the utopian mantras that information wants to be free and the internet is impossible to censor or control?

The fact is that while we are awash in information, there are tremendous gaps in our knowledge of the world. The gaps are growing as violent attacks against the media spike, as governments develop new systems of information control, and as the technology that allows information to circulate is co-opted and used to stifle free expression.

In 2014, I published a book about the global press freedom struggles, The New Censorship. In this year’s edition of Attacks on the Press, we have asked contributors from around the world–journalists, academics, and activists–to provide their perspective on the issue. The question we have asked them to answer–with apologies to Donald Rumsfeld–is why don’t we know what we don’t know.

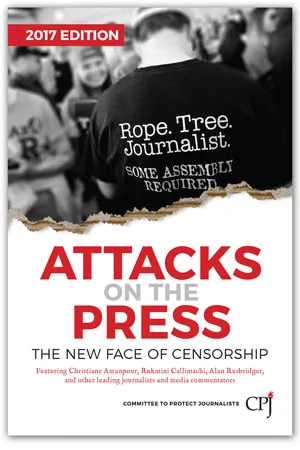

Following the polarizing election of Donald Trump in the United States, concerns were raised about the rise of fake news and the hostile and intimidating environment created by Trump’s heated rhetoric. But around the world the trends are deeper, more enduring, and more troubling. These days, the strategies to control and manage information fall into three broad categories that I call repression 2.0, masked political control, and technology capture.

Repression 2.0 is an update on the worst old-style tactics, from state censorship to the imprisonment of critics, with new information technologies including smartphones and social media producing a softening around the edges. Masked political control means a systematic effort to hide repressive actions by dressing them in the cloak of democratic norms. Governments might justify an internet crackdown by saying it is necessary to suppress hate speech and incitement to violence. They might cast the jailing of dozens of critical journalists as an essential element in the global fight against terror.

Finally, technology capture means using the same technologies that have spawned the global information explosion to stifle dissent, by monitoring and surveilling critics, blocking websites and using trolling to shout down critical voices. Most insidious of all is sowing confusion through propaganda and false news.

These strategies have contributed to an upsurge in killings and imprisonment of journalists around the world. In fact, at the end of 2016 there were 259 journalists in jail, the most ever documented by CPJ. Meanwhile, violent forces–from Islamic militants to drug cartels–have exploited new information technologies to bypass the media and communicate directly with the public, often using videos of graphic violence to send a message of ruthlessness and terror.

In his essay, CPJ’s deputy executive director, Robert Mahoney, describes the global safety landscape and looks at the ways that journalists and media organizations are responding to these troubling trends. The threat of violence is stifling coverage of critical global hot spots from Syria to Somalia to the U.S.-Mexico border, creating a dangerous information void.

Two essays describe strategies journalists are using to respond. As a reporter for the AP based in Senegal, Rukmini Callimachi worked the phones to cover the no-go zones in neighboring Mali, developing sources and an intimate knowledge of the country that allowed her to provide rich, informed coverage once she was able to get in on the ground. Callimachi replicated these efforts to cover terror networks around the world as a reporter for The New York Times. Similarly, Syria Deeply managing editor Alessandra Masi has covered every aspect of the Syrian conflict without ever setting foot inside the country.

The new technologies that allow criminal and militant groups to bypass the media and speak directly to the public have made the world exceptionally dangerous for journalists reporting from conflict zones. But this same process of disintermediation poses challenges to authoritarian regimes around the world that in the past have often managed information through direct control of mass media. Popular movements–from the Color Revolutions to the Arab Spring–have been fueled by information shared on social media, and because anyone with a smartphone can commit acts of journalism, it’s impossible to jail them all.

Finding the balance between the repressive force necessary to retain control and the openness necessary to benefit from new technologies and participate in the global economy is an ongoing challenge for authoritarian regimes. As Jessica Jerreat notes, in North Korea modest cracks are emerging in the wall of censorship, with the opening of an AP bureau and the growing use of cell phones, even if these phones are monitored and controlled. In Cuba, a new generation of bloggers and online journalists criticize the socialist government from a variety of perspectives, and although they face the prospects of harassment and persecution, they are not subject to the mass jailing of journalists in the previous decade.

Outside the world’s more repressive countries, governments generally seek to hide their repression behind a democratic veneer. In his book The Dictator’s Learning Curve, William J. Dobson described how a generation of autocratic leaders uses the trappings of democracy, including elections, to mask their repression. I have dubbed these elected autocrats democratators.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey is perhaps an exemplar, and while his country jails more journalists than any other, in his essay, Andrew Finkel shows how Erdoğan’s government also exercises control over the private media, using direct pressure, regulatory authority, and the law as a blunt instrument to ensure obeisance. Likewise in Egypt, which has seen a massive upsurge in repression, the government of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has expended considerable energy and effort to build a loyal press.

In Mexico, a country that has experienced a democratic transition, an infamous, near perfect record of impunity in the murders of journalists coupled with the manipulation of government advertising and strategic lawsuits have cast a chill over the country’s media, according to New York Times correspondent Elisabeth Malkin. As Alan Rusbridger notes in his detailed report on the Kenyan media scene, “Murder is messy. Money is tidy.”

These strategies focus on political control and manipulation. But, of course, governments also seek to capture the technology that journalists and others rely upon to disseminate critical information. These same technologies can be used for surveillance, blocking, trolling and the dissemination of propaganda. In her essay, Emily Parker contrasts the approach of China and Russia, noting that Russia failed to grasp early on the political threat posed by the World Wide Web, and thus has been playing catch up. Today, even as Russia struggles to curtail online dissent, it is developing what could be termed offensive capabilities, using the internet to spread propaganda and manipulate public opinion domestically and around the world.

Other governments, including China, are also innovating. One of the most dramatic and disturbing examples is the development of a tracking system based on credit scores. As described by Yaqiu Wang, Chinese journalists who post critical content on social media could receive poor credits scores, resulting in loans denied or high interest rates. The government of Ecuador, according to Alexandra Ellerbeck, is alleging copyright and terms of service violations in pressuring Twitter and Facebook to remove links to sensitive documents exposing corruption. Meanwhile, governments, including of the U.S., are promoting the concept of transparency by releasing reams of data which, while welcome, are often of limited utility. And journalists who file freedom of information requests face impediments ranging from delaying tactics to exorbitant fees.

As with any book, and particularly one of this nature, a lot will have changed by the time this edition of Attacks on the Press comes out. Circumstances are extraordinarily volatile around the world, including in the U.S., as Christiane Amanpour and Alan Huffman note in their chapters. Overall, the landscape of new censorship is bleak, and the challenges significant. The enemies of free expression have attacked the new global information system at every level, using violence and repression against individual journalists, seeking to control the technologies on which they rely to deliver the news, and sowing confusion and disinformation so that critical information does not reach the public in a meaningful way.

But the fight is far from hopeless. It is important to keep in mind that the upsurge in violence and repression against the media, and the development of new strategies of repression, are responses to the liberating power of independent information. Technology continues to serve the voices of critical dissent, as Karen Coates describes in her essay on Facebook journalism.

Journalists cannot allow themselves to feel demoralized. They need to pursue their calling and to seek the truth with integrity, honestly believing that the setbacks, while real, are temporary. As Amanpour argues in the closing essay in this volume (adapted from a speech she gave at the CPJ awards dinner in November 2016), journalists must “recommit to robust fact-based reporting without fear or favor–on the issues” and not “stand for being labeled crooked or lying or failing.” This is the best and most important way to fight back against the new censorship.

Joel Simon is the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. He has written widely on media issues, contributing to Slate, Columbia Journalism Review, The New York Review of Books, World Policy Journal, Asahi Shimbun, and The Times of India. He has led numerous international missions to advance press freedom. His book, The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom, was published in November 2014.