In Azerbaijan, an editor is jailed after investigating the unsolved murder of a colleague. The case has opened a window into widespread abuses in this tightly controlled nation on the Caspian Sea.

BAKU, Azerbaijan

Emin Fatullayev is nervous. His son, the newspaper editor Eynulla Fatullayev, has been in prison for a year, and Emin is convinced the family’s ramshackle, one-story brick house on the outskirts of this city is bugged. He leads a visitor to the backyard where, he says, it may be safer to talk. When asked why authorities went to such extremes to prosecute his son, piling up criminal charges from defamation to terrorism and imposing a prison term of eight and half years, Emin lights a cigarette and says it is rooted in a news story–Eynulla’s investigation into the 2005 murder of his boss and mentor, the editor Elmar Huseynov.

“Eynulla found Elmar’s killers,” he whispers, describing his son’s reporting trip to Georgia just months before he was arrested.

Huseynov was shot in the stairwell of his apartment building in Baku on March 2, 2005, in what bore the hallmarks of a contract-style murder. The building’s entrance light was broken, witnesses told CPJ, and telephone lines in the neighborhood were cut. Huseynov, 37, editor of the newsweekly Monitor,was a sharp critic of the administration of President Ilham Aliyev. The weekly closed after his death.

Fatullayev founded the Russian-language weekly Realny Azerbaijan as an editorial successor to Huseynov’s Monitor. He also set out to find his friend’s killers. “Until I draw my last breath, I will be investigating this assassination,” Fatullayev told the newspaper Yeni Musavat.

To mark the second anniversary of Huseynov’s murder, Fatullayev published a first-person piece headlined “Lead and Roses,” accusing authorities of deliberately obstructing the investigation and ignoring evidence that could lead to the masterminds. He said the assassination was carried out by a criminal group that included several Georgian citizens who had been hired by an unnamed official in Baku. Although Azerbaijani officials publicly claimed to be seeking Georgian citizens in the case, Fatullayev wrote that they had not provided authorities in Georgia with arrest warrants or supporting evidence.

Four days after the piece was published, on March 6, 2007, Fatullayev’s mother received an anonymous phone call. As a “wise woman,” the caller said, she should “talk sense” into her son or “we will send him to Elmar.” Fatullayev reported the threat to police, but it was he who came under intense investigation. Eight months later, he was charged, convicted, and sentenced on four criminal counts–the most serious-sounding a “terrorism” charge based on an article in Realny Azerbaijan that analyzed the domestic impact of a U.S. attack on Iran. In the meantime, authorities swept into the paper’s offices and its sister publication, the Azeri-language daily Gündalik Azarbaycan, and issued citations for fire-code violations that effectively shut down both papers.

The case encapsulates the breadth of press freedom abuses in this oil-rich country on the Caspian Sea. A CPJ investigation has found at least eight other serious violent attacks against reporters and editors in three years, not one of which has resulted in an arrest. The government has jailed at least 11 journalists under false pretenses and has moved in to suspend or close at least four critical news outlets in the last five years.

The case encapsulates the breadth of press freedom abuses in this oil-rich country on the Caspian Sea. A CPJ investigation has found at least eight other serious violent attacks against reporters and editors in three years, not one of which has resulted in an arrest. The government has jailed at least 11 journalists under false pretenses and has moved in to suspend or close at least four critical news outlets in the last five years.

With Fatullayev behind bars and other journalists under attack, there is virtually no ongoing scrutiny of the Huseynov murder in the press. The secretive official investigation has yielded no arrests, and CPJ found no tangible evidence of progress. While Azerbaijani authorities have repeatedly said that they have enlisted the help of international police in arresting suspects in Huseynov’s slaying, the public record does not substantiate those claims.

In a recent meeting with CPJ, Aliyev administration officials said two ethnic Azerbaijani citizens of Georgia–Tair Hubanov and Teymuraz Aliyev–are the main suspects in the Huseynov case. “Azerbaijan remains fully committed to solving this terrible crime,” said Arastun Mehdiyev, deputy head of the Department for Public-Political Issues.

But he and Vugar Aliyev, head of the Section on Press and Information Bodies, said Interpol, the international police agency, bears the primary responsibility for apprehending the two men. The officials declined to discuss what Azerbaijani authorities themselves are doing to obtain the arrests, referring questions to domestic investigators at the Ministry of National Security (MNB). The MNB did not respond to CPJ’s written requests for comment.

When Huseynov was killed, President Aliyev immediately condemned the crime, calling it a barbaric act aimed at destabilizing the country ahead of parliamentary elections scheduled that fall. He pledged the murder would be solved within 40 days and invited the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and Turkish agents to join the probe. He soon characterized the crime as a terrorist act, a categorization that would prove significant in the handling of the case.

Pursuant to the “terror” designation, the MNB took control of the case from the prosecutor general’s office in April 2005. That month, several suspects were briefly detained in Baku but were freed for lack of evidence. In May, authorities publicly named the Georgian citizens Hubanov and Aliyev as the main suspects but gave no information about their purported roles. Aliyev has denied involvement; Hubanov has not been located for comment. In the three years since, the MNB has not released photos of the two wanted suspects or disclosed any information about them or their alleged roles.

Azerbaijan reportedly filed requests for the extradition of Hubanov and Aliyev, but on July 28, 2005, Georgia’s prosecutor general said he would not grant any request without being presented with sufficient evidence, the independent news agency Turan reported. Officials in the Georgian prosecutor general’s office did not respond to CPJ’s written requests for information.

In August 2005, Azerbaijani media reported that Hubanov and Aliyev were being sought by Interpol. In one of President Aliyev’s last public statements on the case, he told journalists at a November 2006 press conference that “the murderers are wanted, they have been identified.” As reported by the regional news Web site EurasiaNet, the president added: “However they are not in the country, which makes it difficult to detain them. We are waiting for Interpol to find them to bring them to justice.”

But Interpol’s actual involvement is not nearly so clear cut. The agency’s public database of wanted fugitives does not list either of the suspects identified by Azerbaijani officials. In a written statement, Interpol said it does not comment on specific cases but noted that it issues notices for wanted fugitives, known as “red notices,” only after member countries provide “details of a valid arrest warrant.” Interpol also said that while it assists member countries in locating suspects, it does not itself send officers to make arrests.

Interpol said a member country can request that a fugitive notice not be publicized. That would seem unlikely, however, given repeated public statements by Azerbaijani officials identifying the suspects and asserting that Interpol was looking for them.

Domestically, MNB investigators failed to follow up on basic leads. Huseynov’s wife, Rushana, for example, said MNB investigators were uninterested in her description of a man she had seen following the editor before the slaying. When she approached MNB officials, most recently in the fall of 2006, she said that “they refused to record my testimony or follow up on my accounts. They tried to persuade me that I was wrong and to pressure me to not publicize my conversation with them.” Rushana Huseynov, growing fearful, fled the country.

Eynulla Fatullayev was becoming frustrated. He decided to travel to the Georgian capital of Tbilisi with three other journalists in October 2006 to look for the suspects identified by Azerbaijani officials. In a press conference after their return, the journalists said they had met with Teymuraz Aliyev, who was living openly in Tbilisi, and had taken his photo, which they distributed.

The MNB soon questioned the journalists about their trip. The agency disputed that the man in the photos was Aliyev and warned the four to stop their investigation, according to local press reports. Fatullayev pressed forward nonetheless, giving a series of interviews to the local media. In a November 17, 2006, interview with the independent daily Ekho, Fatullayev cast doubt on the authorities’ good faith in solving Huseynov’s murder. “Law enforcement structures are behaving quite dubiously,” he told the newspaper. “As we uncover something, they try to cover up the tracks.”

A month after “Lead and Roses” ran in Realny Azerbaijan, Fatullayev was imprisoned. Since then, the lack of investigative progress and the absence of information have opened the case to wide and sometimes head-spinning speculation. Ibrahim Bayandurlu, a reporter with the independent Russian-language daily Zerkalo, accompanied Fatullayev to Georgia but came away with a different theory than his colleague. He believes Russian security services were behind the killing as a way to damage Azerbaijan’s image with the West.

Mehman Aliyev, director of the Turan news agency, who has followed the case closely, told CPJ he thinks the murder was organized domestically by would-be coup plotters who served in the presidential guard of the late Heydar Aliyev, father of the current leader. The editor said an MNB official told him that the former guard members were planning to kill prominent journalists and activists to create societal unrest. Elements of this theory have been reported in the local media.

And at one point, in July 2006, an ex-military official even “confessed” to killing Huseynov on the orders of former Economic Development Minister Farkhad Aliyev. The statement was made in open court by Haji Mammadov, a former Ministry of Internal Affairs officer, during his trial on unrelated murder and kidnapping charges. The statement was widely discredited within weeks, though, after the economic minister denied involvement and no evidence emerged to support the assertion. Mammadov has not been charged in the Huseynov case.

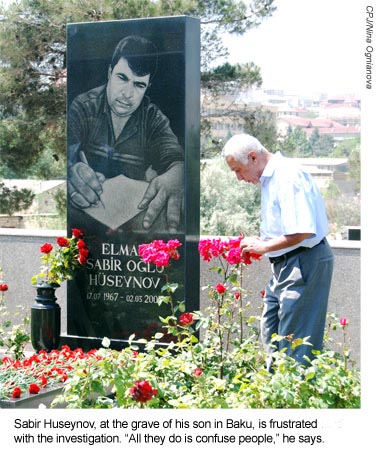

It’s little wonder then that Huseynov’s father, Sabir, appears frustrated when asked about the probe. “What investigation? Three years have passed! What investigation can we talk about?” he says during a visit to his son’s grave. “All they do is confuse people.”

It’s little wonder then that Huseynov’s father, Sabir, appears frustrated when asked about the probe. “What investigation? Three years have passed! What investigation can we talk about?” he says during a visit to his son’s grave. “All they do is confuse people.”

His daughter-in-law and grandson having left the country in fear for their safety, Sabir Huseynov reminisces about the family he hasn’t seen in more than a year and the son he will never see again. “Elmar was not afraid of anything and anyone. He was calling things with their real names. I used to read his magazine and would sometimes tell him: ‘Elmar, maybe you should tone this down a bit, huh?’ And he would say: ‘I can’t. It doesn’t go this way. I would write it as it is or not at all.’ You know, I loved my son, of course. But I loved him twice as much because of Monitor.”

Ilham Aliyev effectively inherited the presidency from his father in 2003 and has since consolidated his position as a supreme executive–maintaining authority over the cabinet, the legislature, the military, and the judiciary. Embattled and fragmented opposition politicians have posed little challenge.

Aliyev is bolstered by his country’s strategic importance to the United States and Europe. Oil in the Caspian Sea basin provides an alternative to Russian and Persian Gulf supplies, and Azerbaijan is a hub in the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Bordering Iran, Azerbaijan provides the United States with a stable, strategic partner in the region. These interests have tended to mute Western reaction to the administration’s human rights abuses.

Domestically, Aliyev’s success is built in good part on his clampdown on the independent media. Television–the most influential news medium in the country–is under the administration’s control either directly or through pro-Aliyev owners. The only independent channel with national reach, ANS, has toned down its criticism of the administration since the state media regulator–the National Television and Radio Council–suspended its license in November 2006. Once back on the air five months later, local journalists told CPJ, ANS changed its editorial content; it no longer gives live airtime, for instance, to opposition politicians.

Low-circulation print media have more editorial freedom, but their impact on public opinion is small. And with authorities cracking down on critical journalists, fewer reporters are willing to cover sensitive topics, the most dangerous of which is reporting on Aliyev and his family. Disgruntled officials use criminal defamation charges frequently, demanding jail time and high damages. The government has resisted persistent calls by international organizations, including the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, to decriminalize libel laws.

Low-circulation print media have more editorial freedom, but their impact on public opinion is small. And with authorities cracking down on critical journalists, fewer reporters are willing to cover sensitive topics, the most dangerous of which is reporting on Aliyev and his family. Disgruntled officials use criminal defamation charges frequently, demanding jail time and high damages. The government has resisted persistent calls by international organizations, including the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, to decriminalize libel laws.

The most critical journalists have also been subjected to violence. Since Huseynov was gunned down in early 2005, CPJ has documented abductions, beatings, stabbings, and other physical attacks against eight independent and pro-opposition journalists. The attacks are all unsolved.

Uzeyir Jafarov, who covered military issues for Gündalik Azarbaycan before it was shuttered, was attacked by two men who struck him on the head several times with a metal object as he was leaving his office on April 20, 2007. Shortly before the beating, he had written articles about corruption in the Azerbaijani defense ministry. Jafarov sustained serious head injuries, for which he was hospitalized. He said he recognized one of his attackers as an officer from the Yasamal District Police Department in Baku and gave the names of five witnesses to police. The witnesses told him that police never approached them. Instead, Minister of Internal Affairs Ramil Usubov said publicly that Jafarov had injured himself. “How can police investigate when the interior minister himself is practically instructing them not to?” Jafarov said.

In May 2006, five men in Baku abducted and beat Bakhaddin Khaziyev, editor-in-chief of the opposition daily Bizim Yol. The assailants drove their car over his legs, leaving him with serious injuries and a lasting limp. There have been no arrests or any apparent developments in the investigation. “When I was attacked, both the president and the minister of internal affairs condemned the crime,” Khaziyev said. “Minister Usubov even said that, for him, solving my case is a matter of honor. But, unfortunately, two years after, there are no results.” Khaziyev said he regularly seeks information from Baku prosecutors and police but gets a standard answer: “The investigation is ongoing.” Shortly before the attack, Khaziyev published articles in Bizim Yolcriticizing high-ranking MNB officials.

Hakimeldostu Mehdiyev, Nakhchivan correspondent of Yeni Musavat, said he was attacked by authorities themselves. On September 22, 2007, several agents with the MNB in Nakhchivan forced him into a sedan, took him to their station in the village of Jalilkand, beat him for seven hours, and warned him to stop his critical reporting, he recounted for CPJ. The next day, police raided his home, arrested him on charges of disobeying law enforcement officials, and took him to a district judge who immediately ordered him jailed for 15 days. In the weeks before his ordeal, Mehdiyev reported on human rights abuses, economic crimes, and corruption in Nakhchivan. He also did a commentary on economic woes and labor abuses that aired on the Azerbaijani service of the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Convinced that the case cannot be properly addressed on the local level, Mehdiyev sent appeals to President Aliyev, the prosecutor general’s office, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the MNB, and the ombudsman for human rights. “They haven’t even answered my letters,” Mehdiyev said.

Azerbaijani authorities have proved efficient at one thing: jailing journalists who work for independent or opposition media. Over the past two years, CPJ research shows, Azerbaijan became the leading jailer of reporters in Europe and Central Asia. At one time in 2007, at least 10 critical reporters and editors were jailed on trumped-up charges such as defamation, drug possession, hooliganism, and terrorism. President Aliyev pardoned several late last year in the face of an international outcry, but at least four remain in prison today.

The government has sought to isolate them and keep them from public view. CPJ’s formal requests to visit the jailed journalists were met with a series of vague and evasive responses: a government fax machine was out of paper; the request was forwarded to the wrong mailbox; the official in charge of making the decision was out of town. The requests, while never officially rejected, were effectively rebuffed during CPJ’s week-long trip in May.

The brothers Genimet and Sakit Zakhidov–journalists with Azadlyg newspaper–are among those in jail. Baku police arrested Sakit Zakhidov, a prominent reporter, poet, and satirist who wrote under the name Mirza Sakit, in June 2006 for alleged heroin possession. Sakit denied the charge and said a police officer placed the drug in his pocket during a staged arrest, but authorities did not question the officer. In October of that year, a Baku court sentenced Sakit to three years in prison. Three days prior to the arrest, Executive Secretary Ali Akhmedov of the ruling Yeni Azerbaijan party publicly urged authorities to silence Sakit. “No government official or member of parliament has avoided his slanders. Someone should put an end to it,” EurasiaNet quoted Akhmedov as saying.

Rena Zakhidov, Sakit’s wife, said her husband’s writing had long angered authorities. His latest book of satirical poems about life in Azerbaijan, titled Ey Dadi-Bidad! (Woe Is Me!), is banned in the country. “No bookstore or vendor would carry it, so I keep the copies here,” Rena said, pointing to boxes stacked in her living room. Rena, who lives in poverty with her five children in a dilapidated house outside Baku, told CPJ that her 12-year-old son, Jahandar, has been harassed by school authorities because of his father’s work, and that she has been turned down from every job she has sought. “Last week, I applied for a job at a pastry shop; they liked my pastries,” Rena said. “But this week they changed their mind. They told me: ‘You understand, don’t you? We just can’t [hire you].'” Rena said Sakit continues to write in prison–on pieces of cloth he tears off his bed sheets and pants.

In another strange scenario, authorities arrested Genimet Zakhidov, Azadlyg‘s editor, on November 7, 2007, after a man and a woman assailed him on the street outside his Baku office building. Zakhidov managed to fend them off with the help of passersby, but the pair went on to file a police complaint. On March 7, 2008, a Baku district court sentenced Zakhidov to four years in prison on charges of hooliganism and inflicting bodily harm, despite contradictory statements from prosecution witness and the absence of any documented injuries, Zakhidov’s lawyer, Elchin Sadygov, told CPJ. Eyewitnesses for the defense were barred from testifying, he said. Nonetheless, Genimet Zakhidov was sentenced to the maximum penalty under the law.

But the Fatullayev case, in particular, illustrates how far the government is willing to go to silence reporters. Authorities creatively used a wide array of criminal statutes–articles of defamation, incitement of ethnic and religious hatred, terrorism, and tax evasion–to ensure Fatullayev remained in custody for a long time.

The terrorism and ethnic hatred charges, which account for eight years of the sentence, stem from a March 30, 2007, Realny Azerbaijan article headlined “The Aliyevs Go to War,” which analyzed possible consequences for Azerbaijan if the United States were to wage war with Iran. The piece sharply criticized President Aliyev’s foreign policy. “There were many articles similar to [Fatullayev’s] already published in the Azerbaijani and the Russian press–and we presented them in court,” Fatullayev’s defense lawyer, Isakhan Ashurov, told CPJ. “Yet only Eynulla was put on trial.” Ashurov said the terrorism indictment alleged that international business people and diplomatic officials had complained about the story. Flimsy as that assertion might have been, no such witnesses even testified. Instead, Ashurov said, the court based its verdict on the testimony of a series of government employees who said Fatullayev’s article “stirred their emotions” and “frightened” them.

The defamation charge stemmed from an Internet posting attributed to Fatullayev– which the editor denies having written–that said Azerbaijanis were responsible for the 1992 massacre of residents of the Nagorno-Karabakh town of Khodjali. “No one could prove that he made the statement. How could they? The whole case was bogus,” said Ashurov, pointing out that under the law an entire class of people cannot be libeled in the first place. “The honor and dignity of Azerbaijanis, as a people, are not protected by Azerbaijan’s laws.”

The defamation charge stemmed from an Internet posting attributed to Fatullayev– which the editor denies having written–that said Azerbaijanis were responsible for the 1992 massacre of residents of the Nagorno-Karabakh town of Khodjali. “No one could prove that he made the statement. How could they? The whole case was bogus,” said Ashurov, pointing out that under the law an entire class of people cannot be libeled in the first place. “The honor and dignity of Azerbaijanis, as a people, are not protected by Azerbaijan’s laws.”

Ashurov said the tax evasion charge was not supported by the evidence, either. The case was put together by prosecutors while Fatullayev was jailed on other charges, making it very difficult to collect records to mount a defense. In June, the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan upheld Fatullayev’s convictions–an unsurprising result, said Ashurov. “Our courts lack independence. … The courts in Azerbaijan are nothing but an empty symbol.”

Shut down by the domestic courts, Ashurov and the Fatullayev family have persuaded the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights to review the case. They are asking the court to overturn Fatullayev’s convictions and pay him damages. As a member of the Council of Europe and a signer of the European Convention on Human Rights, Azerbaijan is bound by the court’s decision. “Strasbourg,” said the editor’s mother, Gulshan Fatullayeva, “is our only hope.”

The Aliyev administration, it seems clear, has little interest in addressing the press crisis created by violence, impunity, and false imprisonment. The troubles, top officials told CPJ, rest with journalists themselves. “One of the main problems of Azerbaijani journalists is that those who enter the profession lack professionalism,” said Mehdiyev, deputy head of the Department for Public-Political Issues. “Most of their problems stem from that.”

Nina Ognianova is CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia program coordinator.

To the government of Azerbaijan

- Release all journalists imprisoned for their work, including Eynulla Fatullayev, Sakit Zakhidov, Genimet Zakhidov, and Novruzali Mamedov. End the practice of jailing journalists in retaliation for their reporting.

- Publicly disclose the status of the investigation into the murder Elmar Huseynov, including the status of arrest warrants, extradition requests, and international fugitive notices. Disclose the specific steps being taken by the Ministry of National Security to identify and apprehend those responsible. Regularly inform Huseynov’s family of the status of the investigation. Ensure that all investigative steps are conducted in a thorough and timely manner.

- Stop harassing critical journalists and their families. End the use of tactics such as pressuring employers to fire or withhold jobs from journalists and their families; damaging family businesses and sources of income through regulatory harassment; and summoning journalists for interrogations following critical stories.

- Decriminalize defamation laws and end the practice of using the criminal code as a means to punish critical journalists.

- Stop using government-controlled media for smear campaigns against critical journalists.

- Ensure that physical attacks against journalists are investigated in a thorough, transparent, and prompt manner. Bring to justice all those responsible for these assaults.

- End regulatory tactics intended to obstruct critical journalists. This includes halting such practices as the refusal to grant broadcasting licenses, the blocking of access to sources and information, and the withholding of press accreditation to independent journalists and media outlets.

- Respect Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Azerbaijan ratified and which guarantees “the right to hold opinions without interference” and the freedom “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media.” Ensure legislation complies with international standards for press freedom.

To the European Court of Human Rights

- Promptly hear the case of Eynulla Fatullayev v. Azerbaijan. Consider all remedies available, including the overturning of convictions and the granting of damages.