Secondary screenings of journalists crossing U.S. borders risk undermining press freedom as Custom and Border Protection agents search devices such as laptops or phones without warrant and question journalists about their reporting and contacts. As the government ramps up searches of electronic devices, rights groups mount legal challenges to fight invasive searches. A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Documentary: Nothing to Declare

Published October 22, 2018

Report Summary

The ability of a government agent to scour a phone or laptop without any legal process is a chilling prospect, particularly for journalists working with whistleblowers. But that is exactly the prospect journalists crossing a U.S. border face thanks to the wide powers granted to Customs and Border Protection agents, who can search electronic devices without warrant, and question reporters about past and current work.

To measure the impact these warrantless searches have on the media, CPJ and our partners at Reporters Without Borders sent an open call to journalists who have been stopped at a U.S. border. We spoke with two dozen journalists and searched news reports and legal filings for public cases. Ultimately, we identified 37 journalists who said they found the secondary screenings invasive. Of these cases, 20 said that border agents conducted warrantless searches of their electronic devices.

While the number of public cases is small compared with the millions of travelers who cross the U.S. border each day, we know that these searches can have an outsized effect. CBP figures show that in the past three years, the agency tripled the number of warrantless electronic device searches it conducts. Journalists told us that these searches and agents’ questions about their current and past reporting are affecting their ability to protect sources and have impacted the way they plan reporting trips and travel. Newsrooms said that they were ramping up security training on digital protection and best practices for staff crossing the border.

The agency is opaque about the data it collects and how it works with other federal agencies. Several journalists told us that a lack of transparency, particularly over information sharing, was particularly worrying.

The potential impact of this is illustrated in documents released in a 2010 case, when CBP—at the behest of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which was working with several other federal agencies–searched the laptop and phone of an activist as part of an investigation into an alleged unauthorized leak of sensitive information. In a separate legal filing, CBP listed “classified information” as an example of the contraband that it has power to intercept.

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees CBP, did not respond to our requests for comment for this report, despite repeated requests.

This is an important time to document the threats that journalists face at the border. At least two bills are in Congress that, if enacted, would restrict the powers CBP has to conduct electronic device searches of citizens and permanent residents. Separately, our partners at the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation are challenging the constitutionality of warrantless electronic device searches in court. Our research shows that a fundamental change is necessary to protect the First and Fourth Amendments at the border, and for no group is this more urgent than the press.

Nothing to declare: Why U.S. border agency’s vast stop and search powers undermine press freedom

David Degner, an American photojournalist who spent years working in Egypt, never expected that the digital security habits he adopted while working in an authoritarian country would be needed while traveling to the U.S. But when a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agent stopped him at a pre-clearance center in Toronto in 2016, the journalist said he found himself demanding that his rights to privacy be respected.

Degner, who has worked for publications including National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine, and The Wall Street Journal, said that when he questioned what right the officer had to demand his phone and passwords, the agent passed him a sheet of paper asserting that CBP—the U.S. law enforcement agency responsible for monitoring points of entry—had authority to examine anything brought into the U.S.

“Luckily I’m used to living in authoritarian countries where police regularly stop people on the streets and demand to see their phones without cause,” Degner said, adding that he handed over his phone after the agent said CBP had power to confiscate it, and was relieved that he was in the habit of wiping his phone of sensitive information.

Over the past nine months, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) have spoken with over two dozen U.S. and international journalists like Degner who said that border agents subjected them to device searches or questioned them extensively about their work. Many said that the searches impacted the way they approach their work and travel, and that invasive searches affect their ability to protect sources or do their job.

The number of journalists directly affected by these stops is minuscule compared with the approximately 1 million people who cross the U.S. borders each day, and only a fraction are included in the less than 1 percent of travelers whose electronic devices are searched. However, conversations with these journalists flagged several issues that threaten press freedom—a right that should be enshrined and protected for everyone who steps foot in the U.S.

The most serious issue is that CBP can, without warrant, gain access to all the information stored on a phone or laptop and share it with other federal agencies. For a journalist, this could expose contact information, notes, images, and communication with, or documents from, confidential sources.

Other issues include a lack of transparency about how CBP collects and shares data with domestic law enforcement and other agencies, and its assertion in a legal filing in December 2017 that classified U.S. information is among the items it considers contraband—a definition that could have serious consequences for journalists increasingly relying on whistleblowers when reporting on politics and national security.

Journalists also said they are confused about their rights, and the processes for requesting answers or seeking redress were often ineffective.

CBP figures show that over the past three years the agency has increased the number of electronic device searches from 8,500 in 2015 to more than 30,000 in 2017. This more-than-threefold increase comes as journalists report being concerned about their ability to protect sources and amid growing hostile rhetoric toward the press. The U.S. government has ramped up leak investigations: The Obama administration prosecuted eight individuals under the Espionage Act, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions has filed indictments in four leak investigations since the start of the Trump administration.

The stakes are high when it comes to government overreach of journalist communications. When the Department of Justice (DOJ) subpoenaed phone records from The Associated Press in 2013, it caused a public outcry. Reporters from the AP, and others covering national security, said that the seizure had a chilling effect on reporting and caused sources to withdraw. In response, the Attorney General issued revised standards for how federal prosecutors can subpoena journalists that recognize the importance of journalists keeping their communications private. But that standard has not been adopted by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

DHS, which oversees CBP, declined to be interviewed for this report, despite several emailed requests for comment. A spokesperson said they would provide responses to a series of emailed questions, but failed to send any follow-up. Requests sent to CBP’s listed email address were returned as “undeliverable.”

A 2018 directive on CBP’s website states that the agency has authority to search devices such as computers, cameras, and cell phones without a warrant; demand passwords; confiscate devices if they are unable to search them; and share information with other federal agencies.

To gauge the impact these powers have on journalism, CPJ and RSF collected firsthand accounts from journalists, as well as cases published in the media or referred by partner press freedom organizations.

We identified 37 journalists who said they found the secondary screenings invasive, 20 of whom reported that their electronic devices were searched. The cases included repeated secondary screenings, warrantless searches of electronic devices, and denial of entry.

Of these cases:

• Between 2006 and June 2018, the 37 journalists were stopped collectively for secondary screenings more than 110 times.

• Cases included U.S. citizens and international journalists, freelancers, and staff.

• Four were questioned as they left the U.S.

• Nearly all of the 20 journalists whose electronic devices were searched said agents took the equipment out of sight. More than half of those (11) were U.S. citizens.

• Three prevented device searches by asking border agents to call their newspaper’s legal counsel or by refusing on the basis of journalistic privilege.

• Thirty said they were questioned about current or past reporting.

The research comes amid increased attention to border stops and electronic device searches. Lower courts are split on the legality of suspicionless device searches and, while the Supreme Court has yet to weigh in, recent court rulings recognize that electronic devices—with their capacity to store the entire digital life of a person—are categorically distinct from other possessions. Robust legal challenges, including a case brought by the ACLU and Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), are progressing through the courts and legislation is in Congress that would restrict warrantless searches of devices belonging to U.S. citizens and permanent residents.

Privacy issues linked to warrantless border stops affect any person traveling in or out of the U.S., but legal experts say that CBP’s powers jeopardize the work of groups including journalists, lawyers, and medical professionals. Although the agency’s directives state that additional supervision from its lawyers is needed when searching information protected by attorney-client privilege, this policy is not extended to the media.

Journalists’ travel patterns can sometimes flag them for a secondary screening, and standard procedure is for border agents to question people about recent travel and work. But questions about past or current reporting appear more significant when placed in the context of CBP increasingly being engaged on issues of national security and intelligence gathering.

Requests by the agency to join the Intelligence Community—a coalition of 16 federal agencies that coordinate and share intelligence—have been revitalized under the Trump administration, according to news reports. Such a development would strengthen journalists and rights activists’ concerns about how data collected by CBP may be used in wider intelligence operations.

The potential impact of invasive searches is being felt by newsrooms. The general counsel for BuzzFeed and The Wall Street Journal told CPJ they were training staff on how to prepare for crossings into the U.S., including minimizing the number of devices and the amount of sensitive data that they carry.

And journalists subjected to repeated stops have adapted how they work. Some said their experiences made them change flying or reporting patterns to try to limit the risk of invasive searches. Some revised their digital security but remain uncertain if their data was copied or sources compromised. Many lamented that they simply didn’t know their rights.

Anne Elizabeth Moore, an American freelancer based in Detroit, reports on groups who say they are discriminated against at border crossings. When CBP stopped her last year and ordered her to leave her phone on and unlocked on her car’s dashboard, “There seemed to be no wiggle room to refuse,” Moore said.

The experience “probably does affect all of my decisions in terms of the stories I pursue and how I travel,” Moore said. “I do try to route myself so I don’t have to have border crossings, which costs me a lot in both time and money. And I haven’t pitched any freelance projects that would have me reporting in Canada.”

And Laura Poitras, the American documentary filmmaker best known for her work with National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, said she moved out of the U.S. for two years to edit her films “Citizenfour” and “Risk” because of repeated stops. “I didn’t feel at that time that I could safely cross the U.S. border and protect the sources that had put their trust in me,” she said.

When Poitras was traveling from Yemen to New York in 2010, border agents at John F. Kennedy Airport confiscated her laptop, cameras, and cell phone for 41 days. Poitras said she now avoids traveling with electronic devices or raw footage, and has spent significant time and resources on her digital security. “It backfired on them,” she said, “because [the stops] made me really good at encryption, which made it possible for me to break the NSA story.”

Journalists at risk

Many of the 37 cases identified for this report were among journalists who travel to the Middle East or report on terrorism or national security—all factors that increase the likelihood of being stopped. Mac William Bishop, formerly a New York Times reporter, said for instance that he was not surprised when agents stopped him and his colleague while they were on their way to Turkey in 2013. They were carrying flak jackets and more than $1,000 in cash.

Arabs, Muslims, and individuals of Middle Eastern or South Asian descent face increased scrutiny at the border, according to the ACLU and other civil liberties organizations. While the data set gathered by CPJ and RSF is not large enough for a representative sample, nearly half of the journalists stopped were of Middle Eastern or South Asian descent, and nearly three-quarters had lived, traveled, or reported in Muslim-majority countries.

Several of the journalists said that as well as routine questions, agents asked about their past and current reporting.

Canadian journalist Ed Ou said that when he was stopped on his way to the U.S. to cover the Standing Rock protests in October 2016, many of the questions concerned his interest in covering indigenous groups in America, and that an officer told him “covering a protest is not a valid reason to come into the country.”

“Having worked in authoritarian countries with very little press freedoms for most of my career … I was accustomed to securing all my electronics before traveling and crossing borders with the assumption that anything I had on me could be used against me or my sources,” Ou said. “That said, I was never prepared to have to do this in a liberal democracy like the U.S., which claims to protect press freedoms and freedom of expression.”

Ultimately, border agents denied Ou entry to the U.S. after he refused to give them the passwords for his electronic devices.

Several of the journalists said that the agents’ ability to access texts, emails, and contacts made them wary about their ability to protect sources.

French-American photojournalist Kim Badawi, who originally wrote about his case for HuffPost, said that when he landed in Miami from Brazil in 2015, border agents scrolled through his phone and questioned him about WhatsApp messages with a Syrian refugee. Jeremy Dupin, an Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker and plaintiff in the ACLU and EFF lawsuit, was stopped twice in December 2016 when returning from reporting in Haiti. Dupin told the ACLU that agents demanded that he unlock his phone, and questioned him—a Haitian citizen and U.S. permanent resident—about his reporting, communication with editors, and photographs taken on assignment.

And agents at a pre-clearance center in Toronto in March 2017 questioned Zainab Merchant, an American graduate student in journalism and international security at Harvard University, about an article on her blog describing a previous border stop experience, according to the ACLU. Merchant is also a plaintiff in the ACLU and EFF lawsuit, Alasaad v. Nielsen.

Multiple journalists said that they did not understand their rights, including Jeffrey Gettleman, then East Africa bureau chief for The New York Times. Gettleman said that when he was stopped in New York’s JFK airport in July 2016 while traveling to the U.S. from Nairobi, Kenya, with his family, he “didn’t know at what point I could stop answering questions and if I could keep my equipment private.” Gettleman added, “I have a lot of sensitive information given to me in confidence and information from people across the world who did not want their identity revealed, and I did not want that to be compromised.”

When the agent asked to examine his phone and laptop, Gettleman refused, saying that it was company property and that the officer would need a warrant.

Maria Abi-Habib, an American and Lebanese reporter formerly with The Wall Street Journal, was stopped in Los Angeles while returning from Lebanon in 2016. Abi-Habib said she was able to prevent agents from searching her electronics by telling them to call the Journal’s legal counsel.

While these two had success refusing demands to unlock devices, others said they had their complaints ignored or felt powerless to refuse. Freelancers who lack the backing of a company and foreigners who can be denied entry are particularly vulnerable. A British journalist, who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized by his employer to speak, told CPJ that an official who stopped him in Chicago O’Hare International Airport in 2017 said the border agency had the authority to force the journalist’s finger on to his phone’s home button to unlock it if he refused to do so voluntarily.

CPJ was unable to verify if the border agency does have power to force a biometric scan. DHS, which oversees the agency, did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment on this report.

Several of the international journalists said they were concerned that refusing a search could jeopardize their visa or immigration status or that they could be denied entry entirely.

An international freelancer, who has reported in Syria and asked to remain anonymous to avoid potential visa repercussions, said, “I treat the U.S. as almost a hostile state … You do or say what you have to to maintain that privilege because the financial cost of not being able to access the U.S. is huge.”

The reporter, who has been stopped twice, said, “When I’m in the states I’m very cautious of what I do or say. I don’t want to say anything about U.S. politics, or do interviews with people that the government may not like, which would put me in the sights of law enforcement more.”

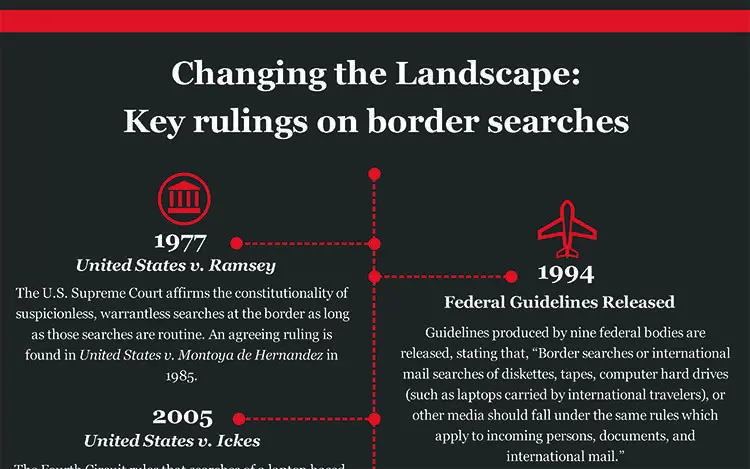

Click to reveal: Infographic: Key rulings on border searches

Legal status

Courts have so far upheld the so-called “border exception” to the Fourth Amendment’s requirement that authorities obtain a warrant to search people and their belongings. But legal challenges are being mounted over whether physical objects—such as laptops and phones—and the digital information contained on these devices should be treated the same way.

Senators have also introduced at least two bills that would require stricter standards for border agents when searching devices belonging to U.S. citizens and permanent residents. The Protecting Data at the Border Act would require CBP to obtain a warrant and the Leahy-Daines Bill would require CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement to have reasonable suspicion prior to basic or “manual” searches and a probable cause warrant for advanced or “forensic” searches. Both have been referred to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

The Supreme Court has ruled on privacy of electronic devices, outside the context of the border. In Riley v. California in 2014, the court restricted authorities’ ability to search cell phones seized during an arrest without a warrant, drawing a distinction between the search of digital contents and that of people and material possessions. “Modern cell phones, as a category, implicate privacy concerns far beyond those implicated by the search of a cigarette pack, a wallet, or a purse,” the court ruled. It also ruled that while officers can search possessions and persons during an arrest to protect officer safety and preserve evidence, that power did not extend to searches of digital devices.

Civil liberties advocates argue that the framework the Supreme Court used to create a warrant exception at the border no longer works when applied to electronic devices. Historically, the Supreme Court balanced what it saw as travelers’ low privacy interest in their luggage against the government’s high interest in border security and contraband.

“It’s self-evident that travelers’ privacy interests in the vast amounts of digital data [their] electronic devices contain are unprecedented. A suitcase can’t hold what a 256-gigabyte smartphone can. And traditional contraband can’t be hidden in digital data,” Sophia Cope, an attorney with EFF who is involved in a suit against DHS over device searches, told CPJ.

Lower courts have staked out different positions, although two courts recently held that the border agency needed reasonable suspicion to conduct forensic searches of electronic devices.

CBP in January revised its policy to more closely align with these rulings. The agency now divides its searches into basic or advanced. For a “basic search,” which includes requesting passwords and manually examining an electronic device, the guidelines state that agents conduct a search “with or without suspicion.” For an “advanced search,” in which agents connect external equipment to a device to gain access and “review, copy, and/or analyze its contents,” the guidelines state that agents should conduct the search in the presence of a supervisor and have reasonable suspicion, a legal standard that courts have held to be less than probable cause but more than “inarticulate hunches.”

In its analysis of the updated policy, the Knight First Amendment Institute said the policy offered “thin protection.” The institute found that the directive “[Still] permits CBP officers to scroll through a traveler’s cell phone, reading personal emails or texts and perusing personal photos and contact lists, on the basis of no suspicion whatsoever.”

Journalists with whom CPJ spoke said they were frustrated that once their devices were in CBP hands there were few safeguards to prevent data—contacts, documents, correspondence, notes—from being shared within the government.

Ahmed Shihab-Eldin, a Kuwaiti-U.S. citizen who works for Al Jazeera Plus and has been stopped five times, said, “When they take my devices, I think about my sources, and I think, ‘Did I save their number? What did I put their name in as?’” The journalist, who has previously written accounts about being stopped, added, “I talk about things that are extremely sensitive. I don’t want them to know who is in my phone … the people themselves might be powerful people in positions working to challenge policies being enforced by the government itself.”

Lawsuits and FOIA requests show that CBP has conducted device searches at the behest of other agencies that can submit a “lookout” or a request to stop an individual for additional screening. Requests also show CBP has previously shared data with other agencies such as ICE, which has a wider mandate and looser data retention restrictions.

U.S. Senator Ron Wyden asked DHS nominees in 2017 how many requests are made by other agencies. Wyden’s office told CPJ in early October that they are continuing to seek more information from CBP about device searches at the border, including a thorough answer to his questions.

Esha Bhandari, an ACLU staff attorney, said that the ability for domestic law enforcement to flag travelers for device searches was troubling. “It means they’re doing an end run around domestic requirements of getting a warrant to search a suspect’s phone.”

CBP’s directive outlines some guidelines for how it handles information, including that it shares terrorism information with relevant agencies. CBP also shares information when seeking assistance about a national security matter or it has reasonable suspicion of activities in violation of the laws it enforces. The directive says the agency’s policy is to delete data if a search finds no probable cause for the seizure. However, privacy advocates said that the protections offered are insufficient. “A significant deficiency in the CBP guidance is the fact that it does not prohibit searches for domestic law enforcement purposes or at the request of other agencies,” Neema Singh Guliani, a lawyer with the ACLU, told CPJ.

Cope, from EFF, said, “The storage capacity of electronic devices is only increasing, ensuring that more and more of our private lives can be found on them. And the government’s interest in this data clearly isn’t waning, given that border device searches have increased … Some judges and members of Congress have recognized the huge constitutional problem this presents.”

No Warrant Needed

At a time when the U.S. government is proactively prosecuting and investigating leakers and whistleblowers, CBP’s ability to search devices without a warrant, and other agencies’ ability to access the data collected, has huge implications for press freedom.

While it didn’t involve a journalist, in at least one instance, government agencies collaborated to stop and search a person connected to a whistleblower case. Documents the ACLU received in 2013 as part of a settlement in a case involving David House, a computer programmer and founding member of the Bradley Manning Support Network, show that Homeland Security Investigations—a subdivision of ICE—filed a “lookout” in the agency’s internal database telling CBP to stop House.

In addition to the search of his devices—including a laptop and camera that were retained for a month—border agents in Chicago questioned House during the November 2010 stop about his association with WikiLeaks and Chelsea Manning, who at that time was charged and in jail.

Partially redacted documents provided to the ACLU of Massachusetts as part of the settlement said that House was “wanted for questioning re leak of classified material” and that CBP officers should “conduct full 2ndary subj &bags secure digital media.” The documents show that CBP shared House’s data with the Army Criminal Investigative Division, which also searched his devices as part of its investigation into Manning.

“House’s case provides a perfect example of how the government uses its border search authority to skirt the protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment,” wrote Brian Hauss, a staff attorney with the ACLU. “The seizure of House’s computer was unrelated to border security or customs enforcement. It was simply an opportunity to conduct a suspicionless search that no court would ever have approved inside the country.”

Bhandari, from the ACLU, said that the House case and similar ones involving journalists show “how a regime of warrantless device searches at the border could be used by the government to single out journalists, to single out people with a viewpoint that the government disagrees with.”

A FOIA filed by EFF found that filmmaker Poitras was stopped as part of an FBI investigation into whether she had knowledge of a 2004 ambush in Iraq. Despite a letter in 2006 in which Army investigators told the FBI they had no evidence that Poitras had committed a crime, she was stopped more than 50 times between 2006 and 2012 as part of an open intelligence investigation.

Poitras told CPJ that she believes this might have been in part a way to gather general intelligence or may have been related to her work related to WikiLeaks. In the U.K., which has similar policies at the border, agents in 2013 detained David Miranda for nine hours and confiscated his electronics, including an encrypted hard drive containing 58,000 classified U.K. intelligence documents to aid his partner Glenn Greenwald’s journalistic work. Greenwald told CPJ in 2013 he believed his communication was under surveillance, and that it was therefore likely that agencies knew Miranda planned to transport the documents for him.

That the wide authority granted to CBP can be open to abuse is illustrated in a case from June last year, when CBP agent Jeffrey Rambo obtained the travel information of New York Times reporter Ali Watkins while he was temporarily stationed in Washington D.C., and questioned her about her sources.

A few months later, in February 2018, DOJ contacted Watkins to inform her they had seized her phone and email records as part of an investigation into James Wolfe. The director of security for the Senate Intelligence Committee is charged with lying to the FBI about his contact with reporters, including Watkins.

The New York Times reported in July that Watkins has been assigned a new beat away from Washington, D.C. after it was revealed that she was previously in a relationship with Wolfe.

Law enforcement officials said they could find no evidence that Rambo was working officially on leak investigations, according to The New York Times. After Rambo’s actions were made public, the Times reported he was being investigated internally at CBP for improper use of computers. The FBI declined to comment to CPJ.

Mark MacDougall, a lawyer representing Watkins, said it was essential to know if anyone else was aware of Rambo’s actions. “Every journalist–really every citizen–should want an answer to that question,” he said.

Gabe Rottman, director of the technology and press freedom project at Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said, “I can’t think of an innocent explanation for the Rambo meeting in the Watkins case.” Rottman added, “If Rambo was freelancing and felt it appropriate to approach a national security reporter to question her aggressively about her sources, that’s a major problem. And, if Rambo was part of a concerted effort to uncover anonymous sources from journalists, that’s likewise of deep concern.”

“The leak investigation involving Watkins was the first time that the Trump administration has gone after a reporter and seized her records, making it all the more important to know the role Rambo and Customs and Border Protection played in the investigation,” Rottman said.

Waiting for answers

The journalists with whom CPJ spoke said they were frustrated with the lack of transparency or information on searches. Some said that they were stopped every time they came to the U.S. to the point where it significantly affected plans for reporting trips. They said that DHS’s complaint process, or applying for a redress number, were often slow or ineffective in preventing subsequent searches.

Isma’il Kushkush, a former International Center for Journalists fellow, told CPJ in 2016 that the prospect of being stopped and questioned affects his reporting. “Do I want to interview a person or not if that interview could become problematic at the border? It’s concerning that I could become a source for law enforcement if they take my information and contacts,” he said.

All eight journalists who filed FOIA or Privacy Act requests reported being dissatisfied with the initial information provided. Several shared copies of the documents they received with CPJ, in which key sections such as the reason for the stop, notes from the officer conducting the search, or even the section subheadings were redacted.

Four of the journalists said they used the DHS established complaint process or applied for trusted traveler programs.

One reporter said that he received his redress number, but was told it was unlikely that it would have an effect. Another said that they twice applied for redress in the hope that raising their case to DHS would reduce the likelihood of them being stopped. However, they were still reflagged for searches. And a third was stopped for a third time despite being approved for Global Entry. One exception is Poitras who, after significant media attention, has not been flagged for secondary screening since 2012.

Degner, the photojournalist based in the Middle East, said he started the FOIA process after being flagged for two secondary screenings in the past 18 months. “Filing a FOIA does nothing to stop another unwarranted invasive search,” Degner said. “But there aren’t many avenues for me to voice my displeasure. Filing a FOIA request might just show how embarrassing little reason they had to harass me, but I expect they will hide that behind redactions.”

While the 37 cases recorded comprise only a sample of the journalists who cross the U.S. borders each year, their experiences demonstrate the threat to the media’s ability to work. The border also carries significance as being the first point at which a traveler should expect to be protected by the high standards the U.S. has a reputation for defending.

“What the U.S. government does can become a marker or a model for other countries, and if it becomes a condition for travel, that people have to submit their entire digital lives to a government agent, no matter from which country, that’s going to have a real impact on human rights; it’s going to have a real impact on freedom of the press worldwide, the ability of the press to travel and report on difficult situations,” Bhandari, the ACLU attorney, said.

With a more aggressive administration openly hostile to the press and leaks, CBP should implement tighter guidelines to protect the First Amendment rights of all individuals crossing the border. If CBP does not act, it will be up to the courts or legislature to protect reporters and ensure that their rights are upheld.