Syrian journalists have been harassed or imprisoned by the Assad regime as well as threatened or attacked by militant groups such as Islamic State. Ultimately, dozens have been forced to flee into exile. These are four of their stories. A Committee to Protect Journalists special report by Nicole Schilit

Published June 17, 2015

NEW YORK

Over the past year, while global media attention was trained on harrowing cases of abduction and murder of international journalists in Syria, scores of local journalists grappled with similar risks away from the spotlight. Many who had been harassed or imprisoned by the Assad regime early in the conflict were now threatened or attacked by militant groups such as Islamic State.

Ultimately, at least 16 Syrian journalists were forced to flee the country for their safety between June 2014 and May 2015-joining the dozens of journalists worldwide each year who make the difficult decision to leave behind homes, jobs, family, and friends to escape harassment, imprisonment, abduction, or murder in reprisal for their work. Over the year, CPJ’s Journalist Assistance program has aided at least 82 journalists fleeing from 30 different countries. CPJ is releasing its annual survey of journalists in exile to mark World Refugee Day, June 20.

Since March 2011, CPJ has helped 101 Syrian journalists going into exile; in the past five years, the country has seen more journalists flee than any other country in the world.

The story of Syrian exiled journalists is unique because a large number of those who ran into danger while documenting and disseminating the news were not initially journalists at all. Starting in 2011, scores of Syrian men and women picked up pens, laptops, video recorders, cameras, and phones to relay to the rest of the world what was happening in their country, particularly as international journalists were increasingly excluded or endangered.

The Syrians reported for local media centers, news websites, regional outlets, and international publications, covering daily life inside the country as well as the conflict. They did this work at no small risk: Syria has been the most deadly country for journalists for three consecutive years, with at least 83 killed in direct relation to their work since late 2011.

When the dangers became too great, some journalists were forced to leave, often initially fleeing to a neighboring country such as Turkey, Lebanon, or Jordan, where threats and harassment sometimes continued. Eventually, several journalists made it farther west to Germany or France, where they live in safety but experience social and economic hardship.

These are the stories of four Syrian journalists and their journeys into exile.

Awad Alali

Awad Alali, a 27-year-old engineer, began filming protests in his hometown of Dara’a in southwestern Syria in 2011, and his YouTube videos would often be aired by pan-Arab outlets like Al-Arabiya and Al-Jazeera. He joined a media organization and taught aspiring journalists to use cameras and transmit video clips. His reports included the names and circumstances of Syrians killed. Alali received death threats on his Facebook page from supporters of both the regime and extremist groups.

“As a result of our work, our homes were burned and our families were threatened. We would move from place to place in fear of the regime. Every time we would move to a place, we would be in danger.”

In the spring of 2012, agents detained Alali at the Syrian General Intelligence Security Branch in Dara’a for three weeks. He told CPJ he was abused and forced to sign an agreement saying he would not practice journalism.

On July 23, 2012, Alali fled with his wife for Jordan. He worked as a fixer, connecting regional media outlets with his contacts in Dara’a, beforebecoming director of broadcasting for two independent Syrian satellite channels. In June 2013, he started working for the Amman-based Iraqi TV station Al-Abasiya, which was critical of the Iraqi government.

In June 2014, Jordanian authorities raided Al-Abasiya. More than a dozen staffers, including Awad Alali, were arrested on anti-state charges. “We were accused of supporting and promoting terrorism,” he said. Al-Abasiya staff members were eventually acquitted of “terrorist actions via the Internet,” according to a translation of court documents.

In late 2014, international human rights and press freedom organizations including CPJ helped Alali and his wife get to France. From there, the two traveled to Germany, where they live with Alali’s brother and sister.

“I am working on getting asylum and securing it. Life here is hard, it is so hard… In exile, with regards to living in Germany, I am very thankful… However, being far from your country is hard. We are alone. There are a number of refugees, but no real community.”

When asked if he would return to Syria one day, Alali said, “I dream of this. … I long for this.”

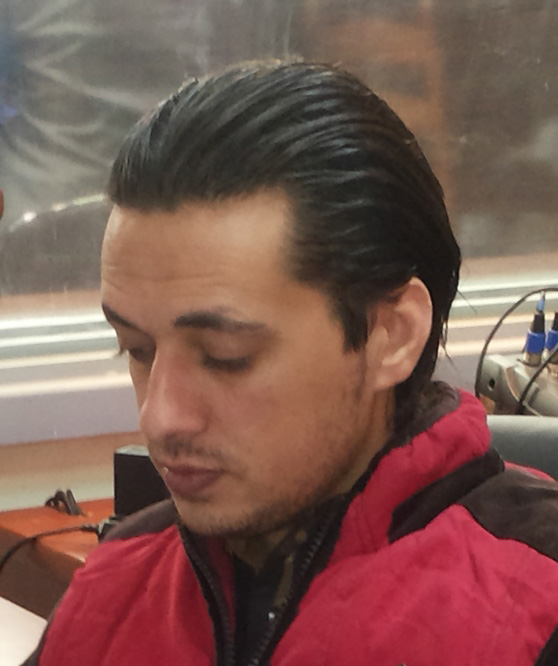

Bassel Tawil

Before the conflict in Syria, Bassel Tawil, 28, was working as a graphic designer, but as protests flared up in 2011, he picked up a camera to document events in his hometown of Homs. He contacted Agence France-Presse, and soon, his photos of life in Homs were published by The Boston Globe, The Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, and other international outlets. Tawil was a founder of Lens Young Homsi, a Facebook page that features the work of amateur and professional Syrian photojournalists and scenes of daily life in Homs province.

In 2012, a friend told Tawil that he was wanted by the government, meaning he could be arrested if stopped by police or soldiers at a checkpoint. Tawil believed he was targeted because he was publishing pictures with his byline. He remained in Homs and continued to take photographs.

In May 2014, during a ceasefire between opposition fighters and government forces, Tawil tried to leave Homs, but was arrested by Syrian authorities and held for 10 days, beaten, and threatened. After his release, Tawil continued to be threatened by security agents. He tried to go to Lebanon, but was turned away because his national ID card had expired. When he attempted to renew his ID, officials told him he was banned from leaving the country. Tawil eventually reached Beirut with the help of a smuggler.

Bassel Tawil continued to face harassment in Lebanon. His identification papers were torn up in front of him at a checkpoint. He was terrified that he would be deported back to Syria so he reached out to Agence France-Presse, who put him in touch with international press freedom organizations that could help him leave Lebanon.

“With the help of [Reporters Without Borders] and CPJ, I was granted a spot at [Maison des Journalistes, a Paris-based residency for exiled journalists]. They are currently helping me with the asylum process. I feel safe now. In Lebanon, I would hold my camera in the street and I would be terrified. But here, nobody looks twice at you when you take a picture. You have the freedom to walk around with a camera here. You can say what you think, what you feel. Nobody will hurt you.

“However, life is very difficult. When I left Old Homs, my state was very bad. … The first few months, I would get scared very easily. I would be startled very easily. Even now, I haven’t fully adjusted to living outside of the siege.

“A lot of people think that photography was a hobby but it’s more than that now. … Now it’s who I am. … I am a photographer.”

Mohammad Ghannam

Mohammad Ghannam, a 36-year-old Palestinian, graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering but turned to journalism in 2011, helping to launch the Syria Today group on Facebook to share news on Damascus.

“People would give updates about what was happening in each neighborhood and city of Syria. It was citizen journalism. We were just trying to publish what was happening.”

In late 2011, someone contacted Syria Today on Facebook, looking for an English speaker. Ghannam volunteered, not realizing he would be working with a journalist from The Washington Post.

One night in 2012, as he was leaving work, Ghannam received a call from a friend who told him not to go home. Syrian security forces had visited Ghannam’s parents’ house looking for him. The journalist left Damascus immediately to avoid arrest. He later learned that his own house had been raided.

Ghannam began photographing events in Idlib and Homs for The Associated Press and Reuters, but didn’t publish his byline with the pictures. In April 2012, on the way to Idlib, he was stopped by government forces.

“The first question they asked me was ‘Why do you have a camera?’”

They pulled him out of the car and beat him.

“They took everything and they took me in. They tortured me and made me confess. My charges were ‘working with the enemy channels’ and ‘making up fake stories,’ ‘organizing protests,’ and ‘blaming the army for the destruction with the pictures I took.’ But I was never formally charged in a court.”

Ghannam was held for more than a year before being released in June 2013. Fearing further retaliation, he left Syria for Lebanon with a smuggler.

In Beirut, Mohammad Ghannam met Anne Barnard, the bureau chief for The New York Times. “I asked her if she needed help, and I began reporting on Syria. She taught me the ropes.”

In November 2014, Lebanese authorities refused to renew his visa. As a Palestinian, he faced extra challenges getting a work permit and residency. Barnard contacted international press freedom organizations on Ghannam’s behalf, and in February 2015 the journalist received a visa to go to France. He lives in Paris and has applied for political asylum.

“I lookedup CPJ’s exile report and saw that only 2 percent of journalists were able to continue their work in exile. … I want to continue working, but I haven’t found the opportunity to do so yet.

“WhenI started it wasn’t because I was looking for a new job, but only to practice my activism in a different way. The journalist is someone who has a message, not someone who is looking to make money. I have a passion for this. This, I feel, is different than working in a factory or an office. You have to have a very specific drive to be a journalist or else you’re dry and empty. My fear is that even if I learn French, it will be hard to work as a journalist. I can learn French, meet French people, order things in French, but it’s different than being able to report and write in French. This is a very specific problem.”

Yasmine Merei

Yasmine Merei, 33, began reporting for the Damascus-based independent online magazine Al Haqiqa in 2012 after she was displaced from her hometown of Homs. She wrote about internally displaced persons and women’s issues.

In September 2012, shortly after she conducted some interviews with displaced individuals, Merei was told by friends that her sources had been questioned by security intelligence. Agents also questioned a friend about her journalism. Later that month, intelligence agents arrested her brothers and father, but Merei did not know if their arrests were related to her work.

In October 2012, government security agents visited Merei and threatened to arrest her. She fled to Lebanon and, a month later, traveled to Gaziantep, Turkey.

Now registered as a refugee there, Merei writes for Saiedet Souria, a Syrian magazine based in Turkey, and the Doha-based newspaper Al-Araby Al-Jadeed. She still receives threats over social media from unidentified individuals.

Leaving family and adjusting to a new country has been difficult. Merei’s brothers are in Lebanon, and her father passed away not long after he was released from custody.

“I think Syrian journalism is important and necessary. [Some] write for an audience and not for the truth. But Syrian journalism is why I have hope for the future, because there are people working and doing and trying their hardest.”

Nicole Schilit is CPJ’s Journalist Assistance associate. She has a master’s in public administration from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and a bachelor’s in documentary photography from Oberlin College in Ohio. Interviews were conducted by Lilah Khoja, an intern in CPJ’s Journalist Assistance program.

All photos courtesy of the journalists.

METHODOLOGY: CPJ’s annual exile report counts only cases who have been supported by the organization’s Journalist Assistance program. CPJ uses this research, combined with expert analysis, to identify global trends. The survey includes only journalists who fled due to work-related persecution, who remained in exile for at least three months, and whose current whereabouts and activities are known to CPJ. The survey does not include the many journalists and media workers who leave their countries for professional opportunities, or to flee general violence, or those who were targeted for activities other than journalism, such as political activism.