Sri Lankan journalists flee under severe pressure in the past year. Iraq and Somalia, two deadly countries for the press, also rank high in numbers of journalists forced into exile. Hundreds of journalists have been driven into exile this decade. By Karen Phillips

Posted June 17, 2009

NEW YORK

At least 11 Sri Lankan journalists were driven into exile in the past 12 months amid an intensive government crackdown on critical reporters and editors, the Committee to Protect Journalists says in a new survey. The surge from Sri Lanka accounted for more than a quarter of the journalists worldwide who fled their native countries in the past year after being attacked, harassed, or threatened with violence or imprisonment.

Nearly 400 journalists have been forced into exile worldwide since 2001, when CPJ began compiling detailed data. Illustrating the extraordinary dangers facing these journalists at home, more than 330 of them remain in exile today. (Click here for complete statistics.)

Data on exiled journalists closely track other press freedom indicators such as deadly violence against journalists and impunity in those attacks. Along with Sri Lanka, Iraq and Somalia rank high among the nations from which journalists fled in the past year. At least two journalists apiece from Pakistan and Russia also sought exile in the past year. All five countries are among the deadliest for journalists and among the worst in solving crimes against the press, according to CPJ research.

“Sri Lanka is losing its best journalists to unchecked violence and the resulting conditions of fear and intimidation that are driving writers and editors from their homes,” said Joel Simon, CPJ executive director. “This is a sad reality in countries throughout the worlds where governments allow attacks on the press to go unpunished.”

Worldwide, 39 journalists fled their home countries in the past 12 months—a decline from a record 82 in the prior year—but consistent with annual figures over the rest of the decade. The decline reflects in large part circumstances in Iraq, where two different forces have been at work. Violence has ebbed, lessening the need to flee, even as a number of Iraqis seeking resettlement in the United States are still in country awaiting approval through a special year-old program.

As in prior years, most journalists who fled their homes in the past 12 months were driven out by violent attack or the threat of assault. At least five journalists who sought exile in the past year were severely beaten prior to their departure, CPJ research shows. Another 24 had received threats against their lives or those of their families.

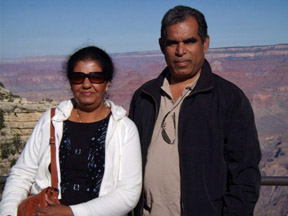

Sri Lankan journalists have faced severe retribution for producing critical coverage of government military operations against Tamil rebels. Upali Tennakoon, editor of Sinhala-language weekly Rivira was driving to his office when four men on motorcycles smashed his car windows, beating him and his wife with metal bars. Though his paper was pro-government, Tennakoon had criticized a high-ranking army official.

• CPJ’s Emergency Assistance

• CPJ Blog: Lives in exile

• Journalists in Exile 2008

Following his release from the hospital, Tennakoon’s wife fielded a menacing phone call urging her husband to quit journalism “or else.” Fearing for their safety, the couple left for California, where they had family to receive them. Tennakoon has followed the investigation of his attack from afar, but no progress has been made. “Without information about who did this and why, I don’t think it is safe to go back,” he told CPJ in a recent interview. At least nine Sri Lankan journalists have been murdered this decade without a single conviction being won against an assailant, CPJ research shows.

A veteran journalist with more than 30 years in the profession, Tennakoon never thought he would leave his country. “My idea was to one day enjoy my retirement in Sri Lanka,” he recalled. Despite his uncertain future, for the moment Tennakoon is glad to be safe. “After my attack I was afraid to go anywhere. Now I have no fear. That is the freedom I have in the USA.”

CPJ is releasing its survey to mark World Refugee Day, June 20, and to highlight the many cases of journalists forced to leave their native countries for doing their jobs. The survey counts only those who fled due to work-related persecution, who remained in exile for at least three months, and whose current whereabouts and activities are known. It does not include the many journalists and media workers who left their countries for professional or financial opportunities, those who left due to general violence, or those who were targeted for activities other than journalism, such as political activism.

Throughout the world, exiled journalists face lengthy bureaucratic procedures as they establish their new legal status, along with significant language and cultural adjustments as they rebuild their lives. Many have difficulty finding work in their profession: Since 2001, CPJ research shows, only about one in three have been able to continue journalism careers in exile.

Freedom from fear has been the sole comfort for journalist Naqeebulla Sherzad, who was granted asylum in Sweden in November 2008 after leaving both his career and his family in Afghanistan. A fixer for foreign media outlets including The Nation and The New York Times, Sherzad first received threats in 2006 after helping a group of foreign correspondents work on a story near his home village in Nangarhar province, near the border with Pakistan.

Sherzad risked his safety again by appealing to contacts for the release of his friend and colleague Ajmal Naqshbandi, who was abducted in 2007. After Naqshbandi’s was brutally murdered, circumstances became increasingly dire for Sherzad as well: His name appeared on a Taliban death list.

At considerable expense, Sherzad traveled to Pakistan and then flew via Dubai to Europe, eventually making it to Sweden by car. At 27, he has left a promising career behind. “I dreamed a lot as a fixer of becoming a journalist to work in the country and improve our profession,” said Sherzad, who once planned to start a news agency with Naqshbandi in Afghanistan.

After a record high number of journalists fleeing Iraq in 2007-08, CPJ research shows the number dropping. Part of the decline is related to improving security conditions. Part is due to journalists awaiting approval from the U.S. resettlement program.

The program, an initiative of the Refugee Crisis in Iraq Act of 2008, which CPJ supported, allows Iraqis affiliated with the United States (including U.S. media outlets) to apply for direct resettlement to the United States from Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt. Though the program marks a clear improvement over prior policies, human rights groups haveexpressed concern that the program, created to expedite the cases of vulnerable Iraqis, is slow moving, resettling just 9 percent of its 15,627 applicants, according to a new report from Human Rights First. CPJ knows of only five journalists who have been resettled to date under the legislation. The precise number of journalist applicants is not clear; the U.S. government has not broken down figures by profession.

Ruthie Epstein, coordinator of Lifeline for Iraqi Refugees Program at Human Rights First, said Iraqis who have applied through the new program can expect to wait one to two years before they can leave—a period during which many must live in hiding to stay out of harm’s way. Epstein has noted that, despite fragile improvements in security, “Baghdad and other parts of central Iraq are still quite dangerous and the nation as a whole is not a safe place for a mass return of refugees.”

Karen Phillips, a freelance writer, is a former associate in CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program.

Journalists in Exile: A Statistical Profile

FOR THE YEAR JUNE 1, 2008-MAY 31, 2009 |

|

|

TOTAL of those who went into exile: |

39 |

|

TOTAL who returned during the year: |

2 |

|

TOTAL still in exile |

37 |

|

THE COUNTRIES FROM WHICH THEY FLED

|

|

|

Sri Lanka |

11 |

|

Iraq |

6 |

|

Somalia |

6 |

|

Ethiopia |

2 |

|

Pakistan |

2 |

|

Russia |

2 |

|

Afghanistan |

1 |

|

Azerbaijan |

1 |

|

Cameroon |

1 |

|

Eritrea |

1 |

|

The Gambia |

1 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

1 |

|

Mexico |

1 |

|

Niger |

1 |

|

Rwanda |

1 |

|

Thailand |

1 |

|

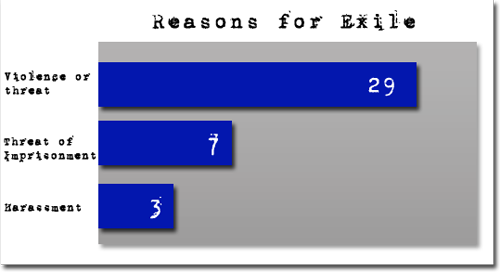

REASONS FOR GOING INTO EXILE |

|

|

Violence or the threat of violence |

29 |

|

Threat of Imprisonment |

7 |

|

Harassment |

3 |

EIGHT YEAR PROFILE: 2001-09 |

|

|

CPJ began compiling data on exiled journalists in August 2001. |

|

| TOTAL of those who went into exile |

389 |

| TOTAL who returned during the year |

53 |

| TOTAL still in exile |

336 |

|

THE COUNTRIES FROM WHICH THEY FLED |

|

|

Iraq |

48 |

|

Zimbabwe |

48 |

|

Ethiopia |

41 |

|

Somalia |

30 |

|

Eritrea |

24 |

|

Colombia |

20 |

|

Uzbekistan |

18 |

|

Sri Lanka |

15 |

|

Chad |

14 |

|

Haiti |

14 |

|

REASONS FOR GOING INTO EXILE |

|

|

Violence or the threat of violence |

195 |

|

Threat of Imprisonment |

94 |

|

Harassment: |

100 |

|

RELOCATION PLACES |

|

|

United States |

120 |

|

United Kingdom |

29 |

|

Kenya |

24 |

|

Sweden |

22 |

|

Canada |

18 |

|

PROFESSIONAL STATUS |

|

|

Exiled journalists who have found work in their field: 111 (33 percent) |

|

| Those who returned home and went back to their profession: 35 (66 percent) | |