A CPJ special report on the struggle for press freedom in the EU

Fighting impunity

CPJ’s 2022 Global Impunity Index found that no one has been held to account for nearly 80% of 263 journalist murders over the past 10 years worldwide. Could the EU play a more active role in the fight against impunity, in particular in cases involving journalists in the EU? Greece’s case illustrates the scope of the challenge. “Investigative journalist Sokratis Giolias, who was killed in 2010, and crime reporter Giorgos Karaivaz, who was killed in 2021, were gunned down in similar circumstances by professional hitmen in the streets and there have been no arrests in either case,” CPJ’s Europe representative Attila Mong wrote in October 2022. “It has been years since authorities provided updates on Giolias, and while authorities say they are looking into what happened to Karaivaz, his family and colleagues are dissatisfied by the pace of the investigation.”180

Some crimes have been partially punished. The hitmen in Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder were each sentenced to 40 years in prison,181 but further legal proceedings are pending against the alleged mastermind and two men who allegedly supplied the bombs. The killers of Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová were also prosecuted,182 with fresh trial proceedings against the alleged mastermind underway at the time of writing this report. In October 2022, a court in Paris sentenced two people to life imprisonment and 13 years respectively for complicity with the attackers against the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo in 2015.183

EU officials have repeatedly called for more involvement of The Hague-based Europol (the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation) and Eurojust (the EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation) in resolving crimes committed against journalists. The September 2021 recommendation on the protection, safety, and empowerment of journalists specifically calls on member states to involve the two institutions in cases related to the safety of journalists. In October 2017, a team of Europol organized crime experts were assigned to help Maltese police investigate Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder. On May 5, 2020, a number of press freedom organizations unsuccessfully called on Malta’s attorney general to request further support from Europol, and in April 2021 the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for “the full and continuous involvement of Europol in all aspects of the murder investigation and all related investigations.” In Slovakia, the Bratislava-based Slovak Spectator praised Europol assistance for its contribution in the case of murdered journalist Kuciak and his fiancée. The publication reported that a Europol forensic investigator extracted data from 12 devices, among them phones and SIM cards of suspects. Another investigator extracted data from other devices that the police seized during house searches, such as hard drives and computers.

The EU also sees its role in fighting impunity more broadly and sets its sights on so-called “serious international crimes” committed outside of its borders, including by the establishment in 2002 of the European Network for investigation and prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes within Eurojust.184 In the same vein, the EU supports International Criminal Court investigations into alleged Russian war crimes – including attacks on journalists – in Ukraine.185

However, some experts feel the EU could do more. “The EU should engage more deeply into supporting procedures related to killings of journalists,” Pierre Hazan, a senior adviser at the Geneva-based Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and founder of Justiceinfo.net, told CPJ. U.S. human rights lawyer Reed Brody, a former Human Rights Watch counsel agrees: “The EU may have a very positive impact, especially if it increases its funding to justice activists in Southern countries,” he told CPJ.

‘Plowing water’

The scope and effectiveness of EU actions in support of press freedom often reflect the gap between the values-based narrative that the EU tells about itself and the reality of how it and its member states pursue their interests.

In private, EEAS officials can admit that their work often looks like plowing water. “It is the fate of most democratic countries’ human rights diplomacy,” an EEAS diplomat who spent a number of years in EU delegations in authoritarian countries told CPJ. “When push comes to shove, economic or strategic interests trump human rights. And we are left with trying to dampen as much as we can the effects of Realpolitik on human rights defenders or journalists.”

The EP’s human rights subcommittee, part of the foreign affairs committee, has been assessing EU actions abroad in defense of press freedom and a draft report186 is due to be finalized in 2023. A preliminary study on the impact of EU actions in the Philippines, El Salvador and Tunisia, presented at a European Parliament hearing in June 2022, has already underlined a number of weaknesses in the array of tools –including démarches, public statements, human rights dialogues, and emergency assistance – deployed by the EU, in particular via its delegations on the ground. However, most of these tools were “under-known and under-used,”187 reported study author Tamsin Mitchell, a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Freedom of the Media at the University of Sheffield. She stressed the need for more training and resources for delegation staff on these matters, and for a thorough review of the implementation by EU delegations of the EU guidelines on freedom of expression online and offline. Her study also underlined the gap between ”the EU’s preference for private diplomacy and civil society organizations’ wish for more public action.”188

The EU’s efficiency and commitment varies considerably from country to country and from one specific period to another. A “doctrine of principled pragmatism” inspires the EEAS, according to Mario Damen, of the European Parliamentary Research Service, “meaning a differentiated approach according to the countries it interacts with and with the aim of enhancing Europe’s strategic autonomy.”189

To be effective and credible, the EU must apply the same criteria to all actors, within the EU and internationally, and actively fight against the pitfall of double standards.

According to CPJ Turkey Representative Özgür Öğret, the EU’s discussions with Turkey on its accession to the union were beneficial to press freedom in the country. “But when things went sour and President [Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan used the migration issue against Brussels, press freedom took a back seat. The EU feared to upset him and its officials mostly refrained from issuing too damning public statements.”

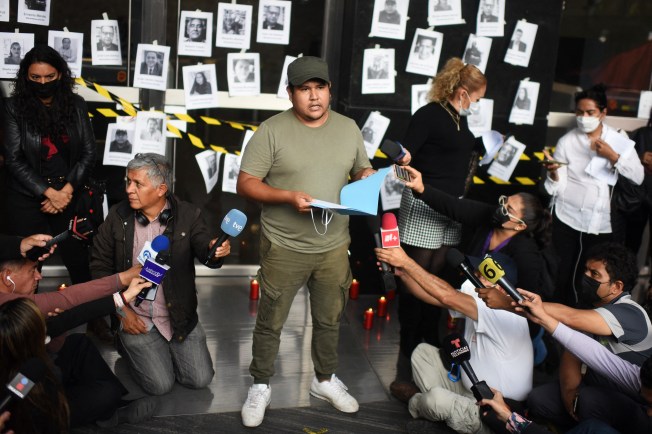

Brussels correspondent Appel confirms that this “pragmatic” approach also applies to Mexico. “Each time something bad happens, the EEAS is very diplomatic and the Council is even more cautious. The European Parliament is the exception, even if it was not always the case.” In an April 2022 article, Appel described the meandering ways of the parliament along the years as MEPs, with their own political interests, blocked Urgency Resolutions.190 A 10 March 2022 resolution condemning “the alarming rate” at which journalists and human rights defenders were being threatened, harassed, and killed in Mexico, however, upset the applecart. The resolution bluntly referred to “institutionalized and widespread corruption, abetted by a deficient judicial system” and to the “Mexican President’s frequent use of populist rhetoric to denigrate and intimidate independent journalists.”191 The EP has become the “new enemy of [Mexican President] AMLO,” Appel wrote.

The corruption scandals involving Qatar and Morocco and a number of subsequent investigations have also revealed the extent of the links, through “friendship groups”192 or consultancies, that some MEPs have developed with authoritarian countries.193

More generally, there is no agreement on how to assess whether EU policies in trade or development may contribute to shaping a toxic environment that puts human rights defenders and journalists at increasing risk.194 The EU has been conducting trade sustainability impact assessments (SIAs) prior to the conclusion of each trade agreement as part of the EU’s sustainable development policy. But human rights organizations remain concerned that trade agreements could have unintended consequences.

EU trade agreements include human rights provisions but most observers agree that they lack effective implementation mechanisms. ”They should be binding like in the Cotonou Agreement,195 where human rights are considered as fundamental and essential elements of the EU-ACP [African, Caribbean, and Pacific regions] relations and can be invoked to suspend non-humanitarian aid,” says a senior adviser of the EP subcommittee on human rights. Human rights dialogues are also often too couched in diplomacy, like check-box exercises with EEAS officials repeating statements with well-trodden EU jargon.

“An effective EU sanctions policy or a better exploitation of GSP [the Generalised Scheme of Preferences, which removes import duties from products coming into the EU market from vulnerable developing countries in exchange for the upholding of human rights standards] might have teeth,” a European Parliament senior adviser told CPJ. “If, for instance, [journalist] Maria Ressa is condemned to jail in the Philippines, the EU could no longer have trade relations like today. The protection of journalists must be specifically part of the GSP+ [Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus] mechanisms,” said one senior official. A revision of GSP remains underway, with some MEPs calling for it to be much tougher.196

Conclusion

The 2019 European elections were an important moment for the EU and press freedom. EU institutions have generally pivoted in a positive direction since the publication of CPJ’s 2015 “Balancing Act” report. Groups including the Committee to Protect Journalists campaigned in 2019 for the European Commission to have a strengthened mandate to work on press freedom. The subsequent media reforms set a positive foundation on paper; but the question is how they will be applied and sustained beyond the mandate of the current Commission, and past the European elections of 2024.

Within the EU, the power of Brussels will have its limitations, at least for the short-term, and it will fall at the feet of EU member states to effectively strengthen national policy on media freedom and journalist protection along the lines of national safety action plans or press freedom reforms, such as in the Netherlands, Sweden, or Slovakia. Yet the test of Brussels’ influence will be the extent to which national measures are then taken up by judicial authorities or law enforcement and whether they will be known by – and have the trust of – the journalist communities in member states.

EU actions do not always trickle down to the journalists it says it is supporting – both in Europe and around the world. The shift in acknowledgement that protecting journalists is a pan-European, cross-border issue has helped, but more sustained support is needed. The institutions of the EU must also strengthen their reputation and integrity, ensuring that all legislation, policy, and communications have, where applicable, press freedom and journalist safety at their core. Until inconsistencies in practice are ironed out, Brussels will have a checkered relationship with media advocates. On the one hand, as the European Parliament moves to address surveillance, on the other, the European Commission threatens the protection offered by encryption. As Brussels funds investigative journalists, it makes access to official documents difficult.

In its foreign relations, the EU has to demonstrate that its member states fully respect press freedom at home or open itself to criticism and accusations of hypocrisy. Coherency in its criticism of third countries, an issue which challenges EU human rights policy more generally, is crucial. To be effective and credible, the EU must apply the same criteria to all actors, within the EU and internationally, and actively fight against the pitfall of double standards.

Such contradictions short change significant actions to advance press freedom and hinder the protection of EU values as a cornerstone of democracy.

Jean-Paul Marthoz is a foreign affairs columnist at the Brussels daily Le Soir. He is the author or coauthor of some 20 books and wrote CPJ’s report on the EU, “Balancing Act: Press Freedom at Risk as EU Struggles to Match Action with Values” (2015). He has also been foreign editor of Le Soir, European press director at Human Rights Watch, and EU correspondent of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Tom Gibson is CPJ’s EU representative in Brussels. His work includes advocating for more effective accountability from the European Union institutions on press freedom. He previously worked for Amnesty International and Protection International conducting research, advocacy, and emergency response or prevention work, covering the Great Lakes region of Africa.

CPJ Editorial Director Arlene Getz edited the report.

Read the full report

- Part 1

– Introduction

– Weak legal arsenal

– Brussels’ new mantras

– Flexing financial muscle - Part 2

– Upholding the law

– Collateral damage

– Encryption

– Guide to EU legislation - Part 3

– Spyware and the EU

– Disinformation

– War in Ukraine

– Trade Secrets Directive - Part 4

– EU access and transparency

– Privacy and the EU’s Court of Justice

– Press freedom diplomacy

– The weight of the European Parliament - Part 5

– Fighting impunity

– ‘Plowing water’

– Conclusion - CPJ’s recommendations to the EU

- Source notes

- Download a PDF of the report