In 1968, Andrei Sakharov braved censorship and personal risk in the Soviet Union to give humanity an honest and timeless declaration of conscience. That same year, Ethiopia’s most prominent dissenter, Eskinder Nega, was born. In January 1981, a year into Sakharov’s exile in the closed city of Gorky, Reeyot Alemu, another fierce, Ethiopian free thinker, was born.

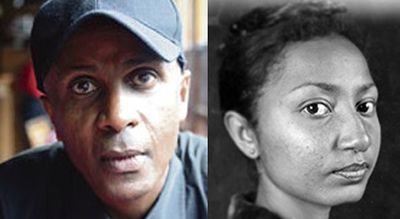

In considering both Eskinder, a veteran journalist and free speech activist, and Reeyot, a teacher and newspaper columnist, for the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize, the selection committee is recognizing two uncompromising idealists and indomitable free thinkers who have stubbornly persisted in telling inconvenient truths about their government in a country silenced by fear.

For Eskinder, who has spent the last two decades in and out of jail enduring arrests, intimidation, the closures of his newspapers, and the arrest of his wife and the birth of his son in prison, you would think fear, anger, and bitterness would be natural emotions. Instead, the writings of the American-educated journalist have consistently reflected a clear commitment to peaceful reform with pointed, thoughtful critiques of the unkept promises of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which maintains a tight stranglehold on the country.

In a 2010 interview–in between two prison confinements–he argued that Ethiopia needs democracy “to moderate the [ethnic] differences” and prevent violent conflict or revolution. Asked whether he believed the EPRDF could reform, his answer was unequivocal: “That’s the only way. We have to hope against hope.”

Then, he added: “I believe in forgiving, by the way, that we shouldn’t have any grudge against the EPRDF, despite what it has done. I believe that the best thing for the country is reconciliation. I believe in the South African experience.”

At the onset of the Arab Spring, Eskinder, inspired by the Egyptian military’s decision not to attack anti-government protesters, wrote an online article urging Ethiopian soldiers not to crush the people, as they had done in 2005, should demonstrations break out. The ruling party and the state security’s overreaction to the column betrayed its paranoid insecurity: a top police official issued a death threat and a final warning to Eskinder, accusing him of inciting the public against the regime.

In a first-person account of the experience, Eskinder wrote that he left the police station hopeful, and heartened to hear one of the officers escorting him say, “We are all children from one country. We are all human beings. Political differences can be resolved by peaceful dialogue, and we don’t have to kill each other.”

A few months later, as the EPRDF invoked a nebulous terrorist plot to round up dissident journalists, lawyers, teachers, and academics, Eskinder aired what weighed on his conscience again. “None of the recent detainees under the terrorism charges remotely resemble the profile [of a terrorist]. Debebe is probably the ultimate antithesis of the fanatic, his pragmatism, his easy nature, defines him,” he wrote, referring to prominent actor Debebe Eshetu. “Neither do journalists Woubshet [Taye] and Reeyot [Alemu] and opposition politician Zerihun Gebre-Egzabher fit the profile. The same goes for the calm university professor, Bekele Gerba.” Just five days after writing those words, Eskinder was arrested, joining Alemu behind bars.

The daughter of a lawyer, Alemu was known for her very sharp reproaches of the societal ills under the EPRDF’s Orwellian system, including dogmatic narrow-mindedness, the stifling of creative thought, and human rights abuses. Alemu attributes her intellectual courage to parents that encouraged her to speak her mind and Arthur Shopenhauer’s maxim that “truth works far and lives long.”

Passionate about education and politics, she taught English at a secondary school and launched a newspaper aptly called Change, before becoming a freelance columnist in Amharic-language newspapers. In 2012, a collection of her articles were published in a book called The EPRDF’s Red Pen, a critical examination of what she deemed as the detrimental effects of the party’s repressive policies on Ethiopian society. The book could be an Ethiopian version of “The Inertia of Fear,” the scathing 1968 commentary on the Soviet system by Valentin Turchin, a Sakharov contemporary and fellow dissident.

The comparison is apt when you consider Ethiopia’s past as a Soviet-style, totalitarian state, and its current reincarnation as an African model of China’s authoritarian, one-party capitalism.

The current rulers overthrew the pro-Soviet regime in the name of establishing what they deemed true socialism and freedom of self-determination. It is a tragic irony that the once idealist freedom fighters have come to use their power to banish journalists, teachers, lawyers, actors, and other intellectuals to a 21st-century gulag for using peaceful means, i.e., writing articles, to demand reform.

It is an irony that was not lost on Eskinder. “Martin Amis wrote, quoting Alexander Solzhenitsyn, that Stalinism (in the 1930s) tortured you not to force you to reveal a secret, but to collude in a fiction. This is also the basic rationale of the unfolding human rights crisis in Ethiopia. And the same 1930s bravado that show-trials can somehow vindicate banal injustice pervades official thinking. Wont to unlearn from history, we aptly repeat even its most brazen mistakes,” he wrote in a letter from prison published in The Independent.

Eskinder and Reeyot’s principled defense of intellectual freedom has exposed the Ethiopian government’s methods of fear and intimidation as crude and impotent. Reading the article Eskinder published five days before his arrest, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and author Carl Bernstein described him as “the embodiment of the greatness of truth, of writing and reporting real truth, of persisting in truth and resisting the oppression of untruths.”

In a note from prison, Reeyot, upon accepting the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Courage in Journalism Award last year, wrote: “For EPRDF, journalists must be only propaganda machines to the ruling party. But for me, journalists are the voices of the voiceless. That’s why I wrote many articles which reveal the truth of the oppressed ones. Even if I am facing a lot of problems because of it, I always stand firmly for my principle and profession.”

Dr. Sakharov would be very proud.